Dear St Michael’s,

We’ve never met before, possibly due to the fact that I’m a human and you’re an educational institution, and such a meeting would be logistically and anthropomorphically difficult for the both of us. Nevertheless, I feel compelled to write to you, because you are on the verge of making a decision that will affect the both of us.

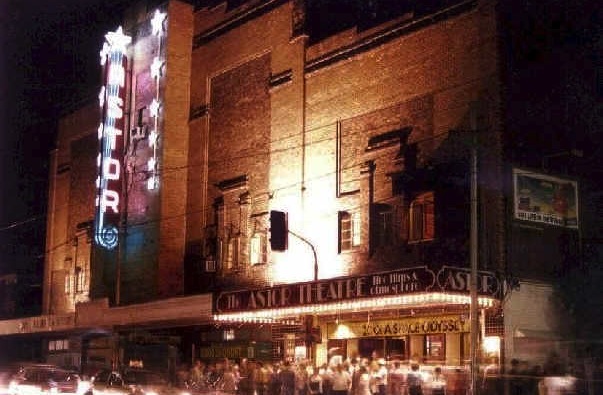

If you don’t know – and I’m guessing you do, but this is an open letter, so we have to assume ignorance on the part of interlopers – a few years ago, you bought the building on the corner of Chapel Street and Dandenong Road. A magnificent art-deco palace that has, for the past 76 years, been the home of The Astor Theatre, an extraordinary single-screen theatre that plays everything from vintage cinema to the latest blockbusters. And yet, it’s so much more than that: it’s an institution. It’s one of the few places you could justifiably call “the heart of Melbourne”. (Although it’s not really situated where the heart would be. Maybe it’s the pancreas of Melbourne. Not as romantic an image, but still a vital organ you really would not want to do without.)

I won’t lie to you. When you bought the building, some of us were a bit nervous. What would that mean for the place that has been so integral to the childhoods, teenagehoods, unnecessarily-awkward twentyhoods, and adulthoods of vast swathes of Melburnians and a surprising number of interstate and international visitors? The last few years have taught me that the formative Astor experiences I thought were so unique are actually universal. There are few people who don’t have at least one important story of life-changing experience that took place within that cinematic cathedral.

Despite our concerns back in 2007, The Astor appeared continued on its journey, and we breathed a collective sigh of relief. This continuation was, it turned out, due to a legally-binding contract and not any form of altruistic charity, but that was of no concern to us. We still had our beloved theatre.

That was five years ago. Now, in 2012, the lease is approaching its expiration, and you guys are moving in. And that frightening sound you heard that followed this revelation was an explosion of community outrage and shock. There were newspaper articles. A massive petition. Somewhat-provocative blogs. There is a forthcoming rally.

You must be wondering what the hell just happened.

I once bought a second-hand car from a guy, and I can tell you that I’d have been quite incensed if, upon conclusion of the transaction, he’d launched a public campaign so he could still drive it around when he wanted. That, by any measure, would have been insane.

So, as you face down a deluge of public negativity the likes of which you have surely never before encountered, I want you to know that I totally understand where you’re coming from.

I totally get that you have a responsibility to your students, teachers, alumni, etc, and that Melbourne Cinephiles With No Actual Connection To St Michael’s is probably further down the list than those of us in that group would like to believe. And you bought that building for a reason; it just makes sense for you to repurpose it.

But you shouldn’t.

In fact, maintaining The Astor in its current form is in your best interest.

As you yourself well know, any educational institution worth its salt is not exclusively concerned with preparing its students for the workforce. Sure, forging a successful career and making money are vitally important skills, but on their own they don’t make for a rounded education or rounded humans. Your own website shows students singing in a choir, experiencing the Transit of Venus, putting on a production of West Side Story, fundraising for children in Uganda… nothing that’s going to get them the CEO job at BP, but incredibly important tools for maintaining their humanity and soul when they find themselves in the dubious position of being CEO at BP.

So how does The Astor figure into this?

You may not know this, but all around the world, cinema is undergoing a massive, unprecedented change. Film is being swapped out for digital in photography, projection and storage. For all the benefits this change offers up – and there are many – there are many, many problems with this, most of which won’t become apparent until it is too late.

The primary one is of preservation.

Digital storage – fast becoming the primary and exclusive method for storing films – is not only more expensive than the storage of physical canisters: it is far more likely to be obsolete. This may seem antithetical, but it is true. (It may also seem hyperbolic. If so, you should read about how close we came to having no footage of the original moon landing.)

But even the supporters of digital-over-film must admit that the change has not been as gradual as it perhaps should have been. The major studios, distributors and exhibitors have backed an almost-overnight switch to the new format, turning traditional film into an historical curio.

Film prints are being digitised and then destroyed. Not sold or given away: destroyed. The ideology that informs such a decision is a frightening one, and comparing it to its obvious historical correlation is probably too incendiary for me to get away with. These prints, once destroyed, can never be recovered. If the importance of this is not hitting you, imagine what would happen if the Louvre announced it would save money on storage by destroying the Mona Lisa and Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin because they’d now scanned them into a computer. The canvas of these pieces is no less vital than the canvasses of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or Leone’s Once Upon a Time In The West or Antonioni’s The Passenger. History is quite literally being demolished by corporations with little sense of an item’s worth beyond the bottom line. And I know using the term ‘corporations’ in this context is often an incendiary pejorative, but it’s an important term because, by its very nature, a corporation tends not to have concerns beyond its own immediate growth. Preserving history and art does not factor into that. Or rather, it will, but by the time this is apparent to them, it will be too late.

Sadly, the number of people within the industry who acknowledge and care about this is too small to have the impact that is needed. And those who do understand the importance do not, on the whole, have an infrastructure available to them to contribute to its preservation. What they have is The Astor.

The Astor has, in fact, managed to upgrade to digital projection – and I say this with my hand on my heart, its 4K digital projection is vastly superior to anything I have seen at any multiplex – whilst still maintaining both 35mm and 70mm projection capabilities. It is the very model of how to embrace the new whilst preserving the old. The Astor takes great care to store film prints that its owners are unable to, and on more than one occasion it has fought tirelessly yet successfully to preserve the last remaining prints of classic movies.

It may seem on the outside as if The Astor is merely one small cinema in a city consumed with wonderful artistic venues, but it is far, far more important than that. It is one of the last remaining outposts in a time of cataclysmic upheaval that has far more dire consequences than most people yet realise.

On Christmas Eve of last year, I went to The Astor to watch a double (projected beautifully on 35mm film) of The Shop Around the Corner (1940) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), two glorious films starring the incomparable Jimmy Stewart. Behind me sat a row of teenagers, and I must confess to a moment of dread when the entered. Would they talk throughout the film? Would their phones come out? Would they be bored?

They were nothing of the sort. They were appreciative, respectful, and – most importantly – engaged. These were kids who had grown up in the age of the internet and smartphones, of frenetically-paced media and attention-destroying pop-culture the like of which we have never seen, collectively enjoying two black-and-white films from the 1940s. Were it not for the legal issues that would have no doubt arisen, I’d have jumped up and hugged them at the end. They gave me a glimmer of hope for the future. And now I wonder if they were, perhaps, students at St Michael’s. It’s not out of the question: they were the right age and they were in the right area. I hope they were.

As a respected and long-standing educational institution, you understand the importance of imbuing your students with essential values. Values that include a respect of the past, an appreciation of long-term worth. And I’m glad you do, because we need more people who recognise the significance of our culture and heritage.

These lessons have, until now, been academic. Now is the time for a practical lesson. Demonstrate how committed St Michael’s is to history, to community, to the arts, to the past and the future.

Your students will receive no greater education.

Sincerely,

Lee

Brilliant. Just brilliant.

As an avid cinema fan, my concern for the preservation of these works I’m certain matches your own. There’s no excuse for destroying film prints (I’m not sure celluloid is as significant to a film as canvas is for an artwork, but I still see your point)? I’m not from Melbourne but by all accounts the Astor sounds like the sort of thing I would want to hang around.

However, the issue that’s been made of digital archival has become s bit of a joke. Kodak’s misinformation has played a big part:

http://motion.kodak.com/motion/Products/Customer_Testimonials/Why_Compromise/archive_one_sheet.htm

Broadly-speaking, the issue of digital preservation is a serious one, in that it requires thought snd the implementation of standards nd practices to meet industry needs. However, th god news is that digital cinema archival hasnt simply been ignored or glossed over, as you and many seem to fear – its actually been an integral part of the DCI (digital cinema initiative) standards and practices from the beginning, and is closely overviewed by SMPTE. The selection of JPEG2000 over H264 as the industry standard coding format for DCPs was less to do with quality and more to do with it’s robustness as a long-term viable format. DCI was concerned with developing standards that would stand the test of time in a similar manner to film standards, despite the ongoing and massive developments taking place in the digital realm. JPEG2000 will not go obsolete. DCI and SMPTE also specify high-quality storage media that isn’t susceptible to degradation (which is bit of a joke really – even cheap consumer grade hard drives will probably last 100 years if stored safely). I’m guessing every ten years or so digital archives will be moved to new media, mainly to account for interface change. While JPEG2000 will be around forever, FireWire and Thunderbolt wont be (but think about how fast Thunderbolt is now and you’ll have some idea how fast it will be to change media in gen years)

I’m a fan of maintaining archival film prints, but people are working hard to impose high standards for digital archive and I think they deserve our appreciation. I’m not trying to be an arsehole, it’s just frustrating there’s a lot of misinformation going around about the subject.

Hello Lee,

What a wonderfully written letter. Thank you so much for writing it to the school.

Best regards,

Brett

Lee, that is brilliant. Everything I have been meaning to say and haven’t been able to put into words.Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Thank-you for writing this wonderful letter.

So pretentious.

Lee, outstanding. Thank you. The Astor thanks you.

FOTA thanks you.

We all thank you.

Beautiful work.

TB

PS to Tom (above me) That is so unfair, unwarranted and mean.

You knob.

Lee – outstanding.

Tom – knob.

Lee, what a really well articulated and heartfelt letter. You have expressed what so many cinephiles feel. Hope The Astor is saved and avoids the fates of venues that were devoted to great cinema programming and such as The Lumiere, The Valhalla and The Carlton Moviehouse. Maybe Martin Scorcese, as a great patron and supporter of preserving cinema’s history, could be enlisted to help out. By the way, really appreciate your work on The Bazura Project and Hell is For Hyphenates. It really gets me thinking critically about film culture.

The preservation of film is important, not just for history but for the shared memories and experiences it offers. I have been going to The Astor since my early 20s and I have been taking my son since he was a young child – he is 19 now and has a love of film that The Astor has helped cement. I treasure our shared experiences at The Astor and would be devastated if we, as a community could no longer step back into the nostaglic warmth of a past era and enjoy film in all its glory.I know my experience will be mirrored by future generations given the opportunity as I listened to one of my Year 12 students tell me of his first visit to The Astor – he spoke with passion and awe – and he will share his joy with others.

Of course the Astor must stay- anything else is a travesty.

Brilliantly said & more… The Astor remains as one of the iconic movie theatres … where people’s diversity comes together as one

just like a ‘true friendship’s trust’ it takes years to build but a minute to destroy!! Preserve it for future generations!!! Westgarth cinemas are also iconic as were the Tivoli in Union rd Ascot Vale Vic.!! Make it more than an avenue where people of all ages come to discuss & enjoy history, art etc.. Lastly… Art Deco is back BIG TIME!!! STOP DELETING HISTORY… OR you’ll delete

the essence of humanity!!

Hi Lee,

As it happens, I’m a parent of a child at the school. Originally from interstate, I can’t claim any personal affiliation with the Astor. However, I had hoped the school would continue as owner and to have been able to share the venue for use of film goers as well as the school community.

I understand that the concerns of the general community eventually outweighed the advantages that the school community perceived by owning the venue, so the venue passed on to another owner.

I haven’t heard any more since that announcement, but I hope that the new owner has provided you and others concerned with the fate of the venue with a level of comfort about the Astor’s future.

I’d love to see a follow up letter.

David.

Hi David

Thank you for your comment, and I agree — it’s a shame there wasn’t a solution that was mutually beneficial to both St Michael’s and The Astor. Hopefully they will still be able to use the facilities there.

There hasn’t been much news since the building was sold to the new owner, and I certainly don’t have any inside information, but my take on the matter is that the new owner is a big fan of the business, and will likely allow it to continue on. Again, I want to stress that this is purely my assumption based on the few snippets of info we got around the time of the sale. I am cautiously optimistic.

I personally think that St Michael’s showed a lot of class in its response to the community’s pleas, and the sentiments in your letter here give me a very high opinion of the families who attend the school.

When there is concrete news about the future of the Astor, I shall definitely put an update here.

Thanks again,

Lee

So, now that the school sold the Astor – essentially due to community backlash over the school’s ownership – to a new landlord, who subsequently announced his intention to close it, how do you feel? Would it not have been better to discuss and negotiate with a school who values community interests rather than a private owner. Or perhaps you could have spent your energies attaining crowd funding to buy it and donate it to a trust who operates in on behalf of the community?

The piece you are commenting on doesn’t call for St Michael’s to sell the building, but asks them to keep the Astor running. I could be mistaken, but I don’t recall many people calling on St Michael’s to sell; if there was, they were a minority next to the voices hoping that the partnership between the business and the school could continue.

I’m not sure why you think nobody was in favour of the Astor negotiating with the school. As memory serves, the Astor was in fact attempting to do just that, and whilst I’m not privvy to the behind-the-scenes discussions, it did appear St Michael’s held all the cards.

I would have much preferred the Astor continue to operate under a landlord that was also an educational institution (as I originally explained in the above piece), but as to whether it’s more preferable that the Astor shut down with Landlord A rather than Landlord B… well, at this stage it doesn’t really matter, does it?

I am flattered you think I could have run a crowdfunding campaign that could have raised the millions of dollars necessary to buy the building (leaving aside for the moment that there was no guarantee St Michael’s would have sold). But the energies I expended in writing a blog post would not have equalled such a venture.