Bedford Falls. A town so idyllic, the FBI thought it might be Communist propaganda.

Christmas just isn’t Christmas without Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), the story of a good man who loses hope and has to be shown the true value he has brought to the world. George Bailey (James Stewart), who loves his town of camaraderie and kindness, is nevertheless frustrated that it’s too small to contain his dreams.

We follow George over the course of a lifetime, see him overcome adversity, and watch as he’s slowly eroded by despair; how every chance he has to get ahead is thwarted either by misfortune or the machinations of local business mogul Henry F Potter. It’s a life of hard work and dashed dreams that eventually robs him of the will to live.

In many ways, it’s the quintessential yuletide tale, which is why it gets a spin in this household every single Christmas. But it’s been an awful lot of Christmases at this point, and after many, many viewings, I think I’ve stopped being able to watch the film in the way I used to. At some point, I crashed through the film’s façade and began to see the meaning that had been hiding under the surface this whole time, the narrative base code if you will, a secret message so diabolical and terrifying it would have given J Edgar Hoover night terrors for the remainder of his paranoid days.

It’s been a few years since I discovered this secret meaning, and I’ve spent a long time debating whether it is ethically responsible to reveal it to the world. Because once you know it, you will be unable to ever un-know it; it will be impossible to ever see the film in the same way again.

In short: if you do not want this lovely film ruined forever, stop reading, and stop reading now, because I am about to take you on a journey down through the strata of It’s a Wonderful Life. Think of me like Dante’s Virgil – a guardian demon, DS2 (Demon Second Class) who is absolutely determined to earn his horns.

If you’re brave enough to join me on this journey, I’d like you to begin by pondering one simple question: who is the real villain of Bedford Falls?

It’s not that difficult a question. The answer seems obvious and uncontroversial, doesn’t it? So let’s start there.

POTTER IS THE VILLAIN OF BEDFORD FALLS

Lionel Barrymore’s Mr Potter is one of the all-time great antagonists. He’s a growling grump, a man who only ever seems happy when basking in the misery of others. He is a robber baron, the quintessential example of someone who sees the cost of everything and the value of nothing. He is the Scrooge who never learns the lesson, and seems so anachronistic in the serene Bedford Falls, you can only assume he was kicked out of some Big City for being too ruthless a bastard.

Just look at the scene that I consider to be the film’s most profound and revealing moment: George comes crawling to Potter for help, claiming to have misplaced a large Building and Loan cash deposit. Potter knows this isn’t true, he knows Uncle Billy is the one responsible, and sits in bewilderment as George – who is furious at Billy – bears the shame entirely on his own shoulders.

Not only does Potter fail to learn any apposite lesson from this supreme virtue, he still tries to needle George, outrageously suggesting George may have spent the missing money on a mistress. When presented with the great and the great, all Potter sees is a world of fools magnifying their own misfortune due to what is, to him, a baffling moral code.

He is, quite naturally, the only reasonable candidate for Bedford Falls Villain. Yet, as we’re about to discover, Mr Potter may be a thief and a scoundrel, but he is no villain.

Normally, this would be the point in the essay where you get Galaxy Brained with the take that the noble George Bailey is, in fact, his own worst enemy; that all of his frustrations are borne of the conflict between his desires and his inner angels, that his lifelong dreams of travel and adventure are thwarted only by his own sense of duty. But I’m not going to do that.

Because there is a flesh-and-blood villain of It’s a Wonderful Life, and it is not George.

Nor is it Mr Potter.

It’s Mary.

MARY IS THE VILLAIN OF BEDFORD FALLS

If we’re going to identify the villain, we need to first be absolutely clear on the identity of our hero, and this one is straightforward: George is the unimpeachable hero of our story, and our hero has but one dream, which is to travel.

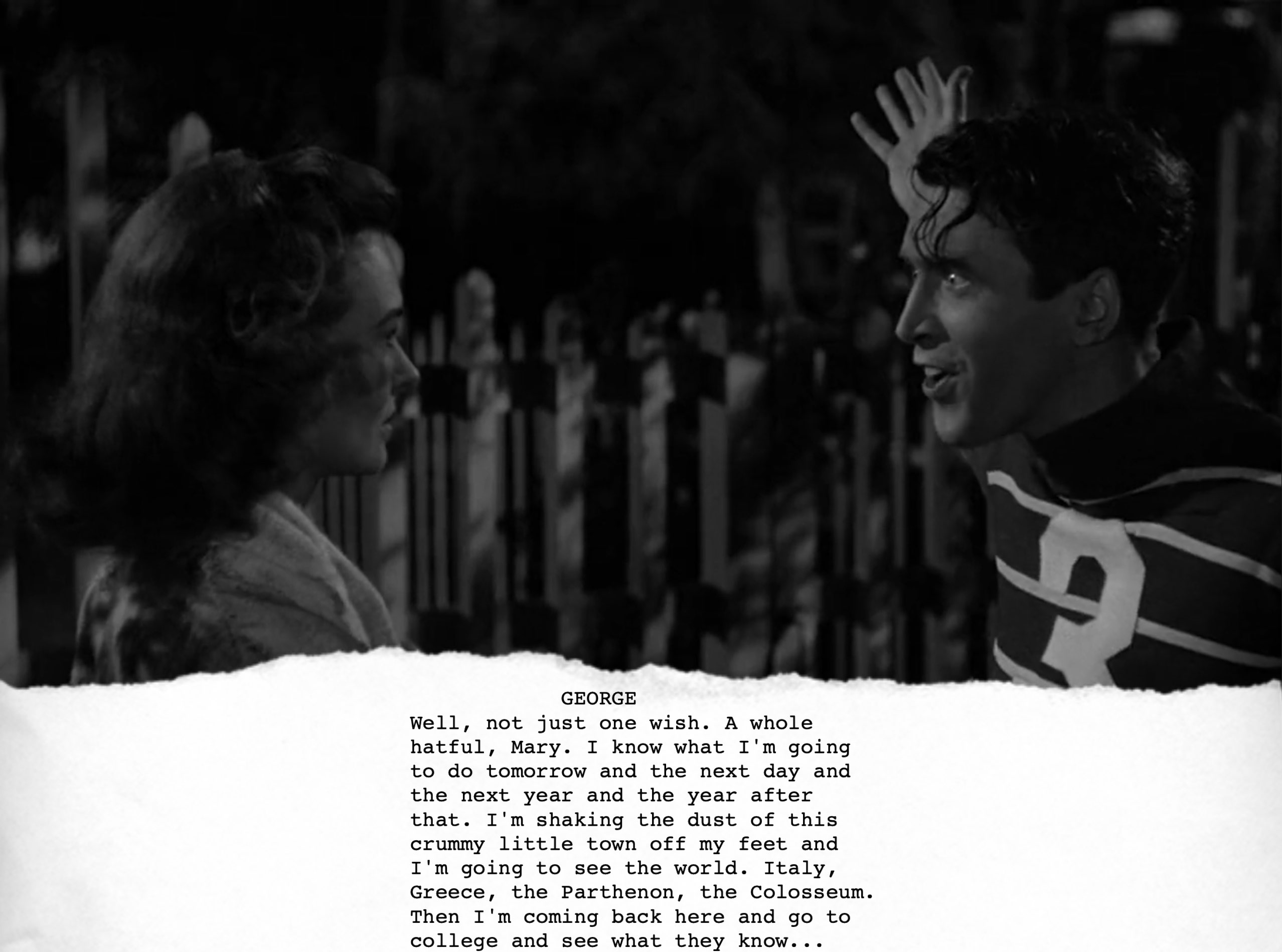

George wants to see the world and get out of Bedford Falls, and no dream has ever been expressed with sure purity of yearning. Every time George speaks about travel, something happens to his face. It opens up with unbridled longing, and we the audience want nothing more for him to achieve this very reasonable ambition.

So who exactly is it that foils him at every turn?

There is one villain, working in often inscrutable ways, to prevent George from achieving his dream, and her name is Mary Hatch (Donna Reed).

Want some tangible evidence to back up this scandalous claim? Let’s start with a forensic examination of every moment George could have left Bedford Falls.

Harry’s Return

It’s 1932, and George is at the train station with Uncle Billy. He’s not just anticipating the return of his brother Harry because he misses him; George knows Harry is coming back to fulfil his promise of finally taking over the Building and Loan. As Harry says, George been holding the bag all this time. It’s his turn to go see the world.

However, when Harry alights the train with both a wife and the promise of a career, George knows full well he can’t stand in the way of his brother’s prospects. But does that necessarily mean he must stay at the Building and Loan? It’s been four years, and our boy’s got plans.

Truth is, we don’t really know which way George is leaning. The big celebrations complicate matters, and he seems genuinely excited for his brother’s fortune. So when Ma Bailey plants the thought in his head to go and visit with Mary Hatch, his uncertainty leads him right to her door. In fact, George seems to be the only one who doesn’t know that’s where he’s headed. Mary certainly knew before he did.

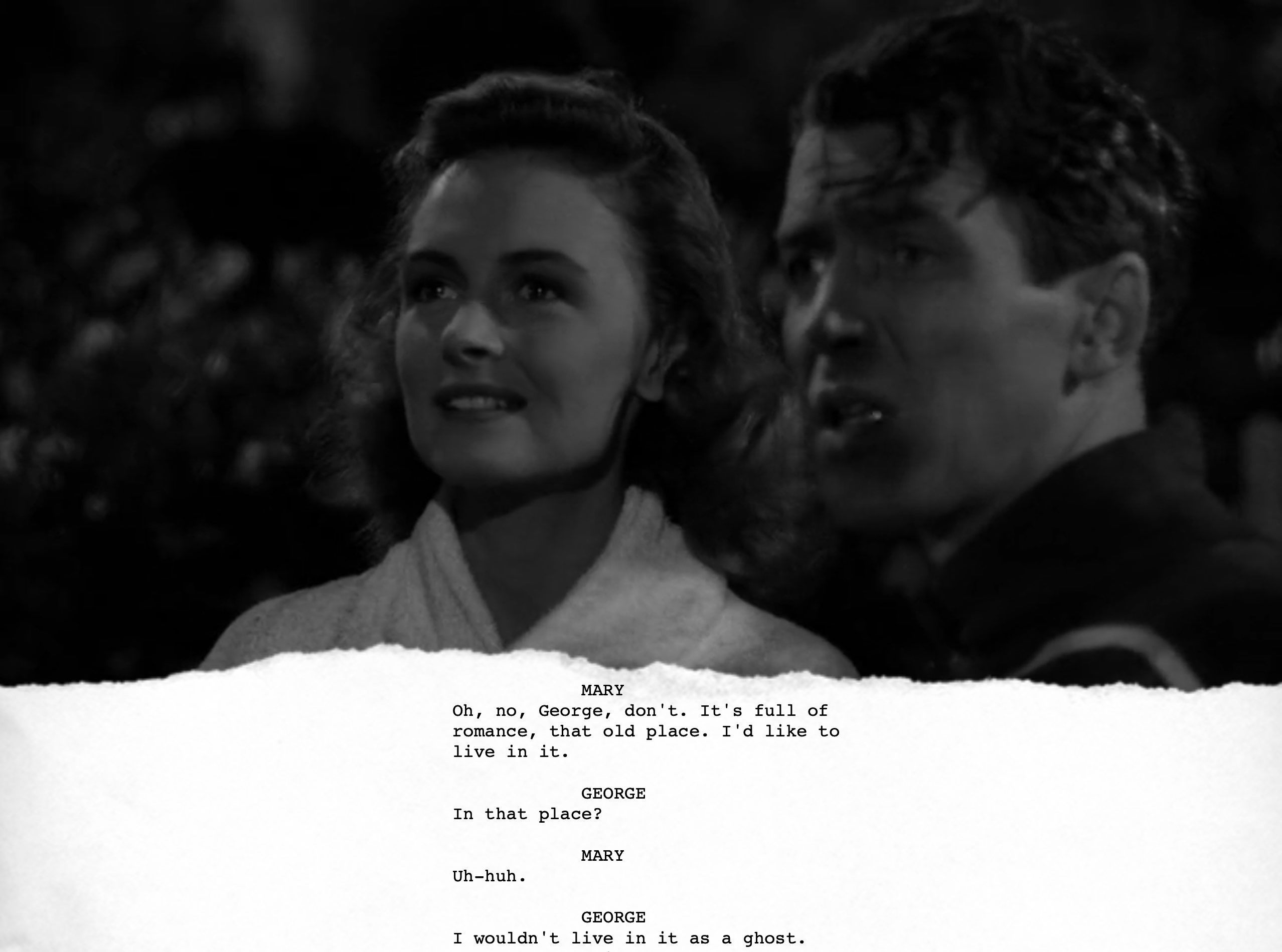

The setup is obvious. Mary is absolutely out to seduce him, and she deploys every trick at her disposal: she reminds him of the song they once bonded over, tries to neg him into admitting he really does want to get married, and pretends to flirt with Sam Wainwright. You may think this is all innocent seduction, but her villainous masks slips when she violently smashes the record like it’s a clumsy henchman, furious the prop’s failure to deliver the goods.

But like all good villains, she doesn’t give up, and finally gets George where she wants him. It’s a vulnerable time for him. He feels trapped, robbed of his future, and the closest thing he sees to adventure is a bold, adventurous decision: he’s going to marry Mary.

She has substituted his desire for travel with a desire for her. He is thwarted.

The Honeymoon

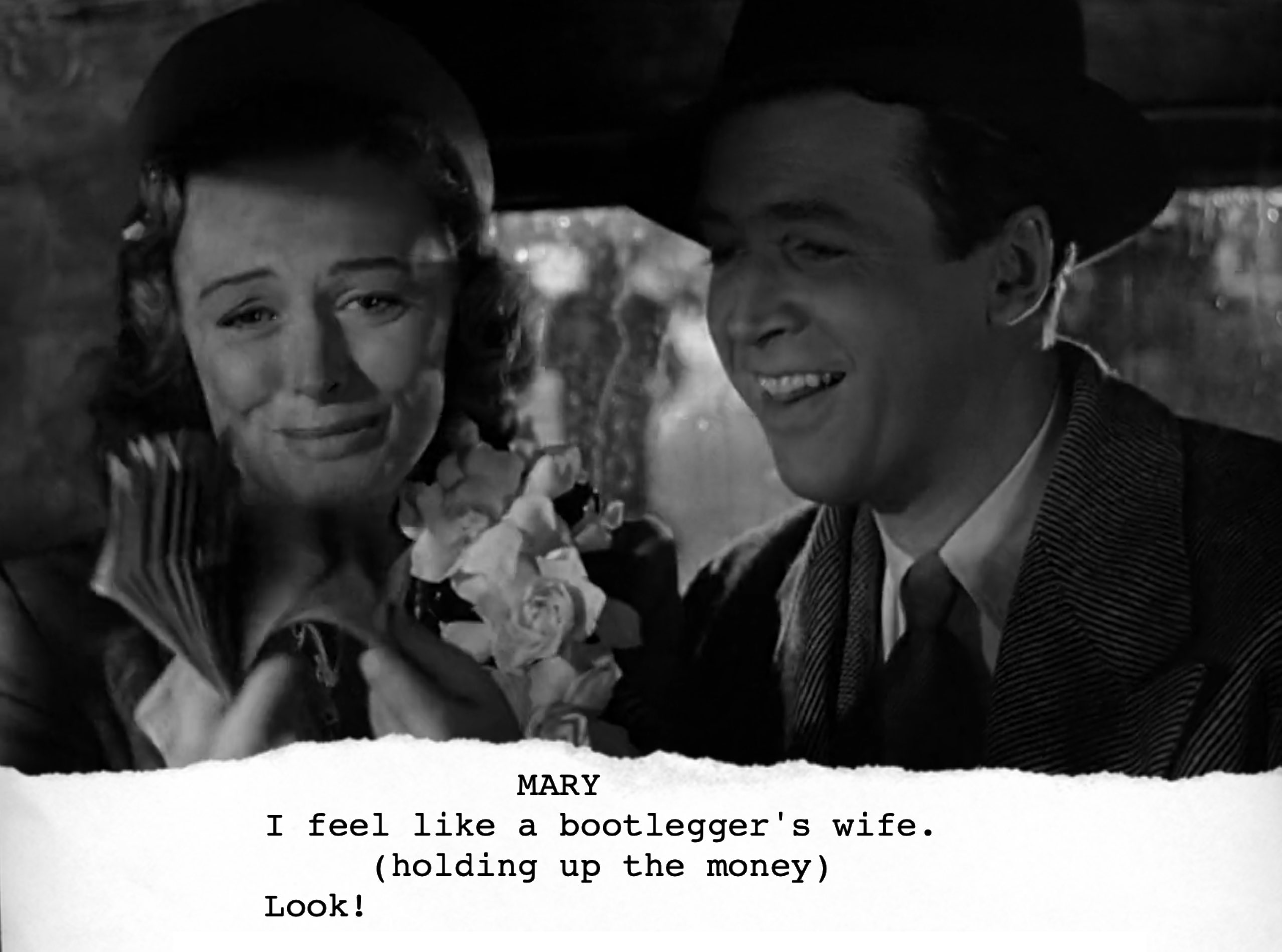

In the very next scene, George and Mary are wedded. George is excited for his honeymoon, and not just for the usual 1930s Hays Code-compliant reasons. He’s finally – finally – heading overseas. George has cashed out every cent to his name, and when they taxi away from the chapel, it’s Mary holding all the money.

They barely make it a block. When they catch sight of the run at the bank and then go to check on the Building and Loan, it’s Mary who comes to the rescue. She’s the one who waves the cash in the air, insisting without hesitation that their travel loot should go to the community.

That’s the moment we realise she is the perfect partner for George. She’s as selfless and caring as he is, someone who will find a creative way to serve the greater good, even at her own personal expense. Even at the expense of her husband’s dreams.

Although this action means George’s plans are instantly derailed, you may believe her altruism runs counter to all this alleged nefarious plotting, that she couldn’t possibly have planned all this… to which I say this: skip forward to the end of the night. George has put the last two dollars he has left in the safe when he gets a call telling him to go home. Which home? The Old Granville House.

He turns up to discover Mary has made them a home in the abandoned house, which she now inexplicably owns. At what point in the evening did she bid for and then successfully close the deal on this house? With what money? What’s the timeline here?

There’s only one way it makes sense: Mary bought the house before their wedding day.

She never intended to leave Bedford Falls, and she never intended for George to either.

The Job Offer

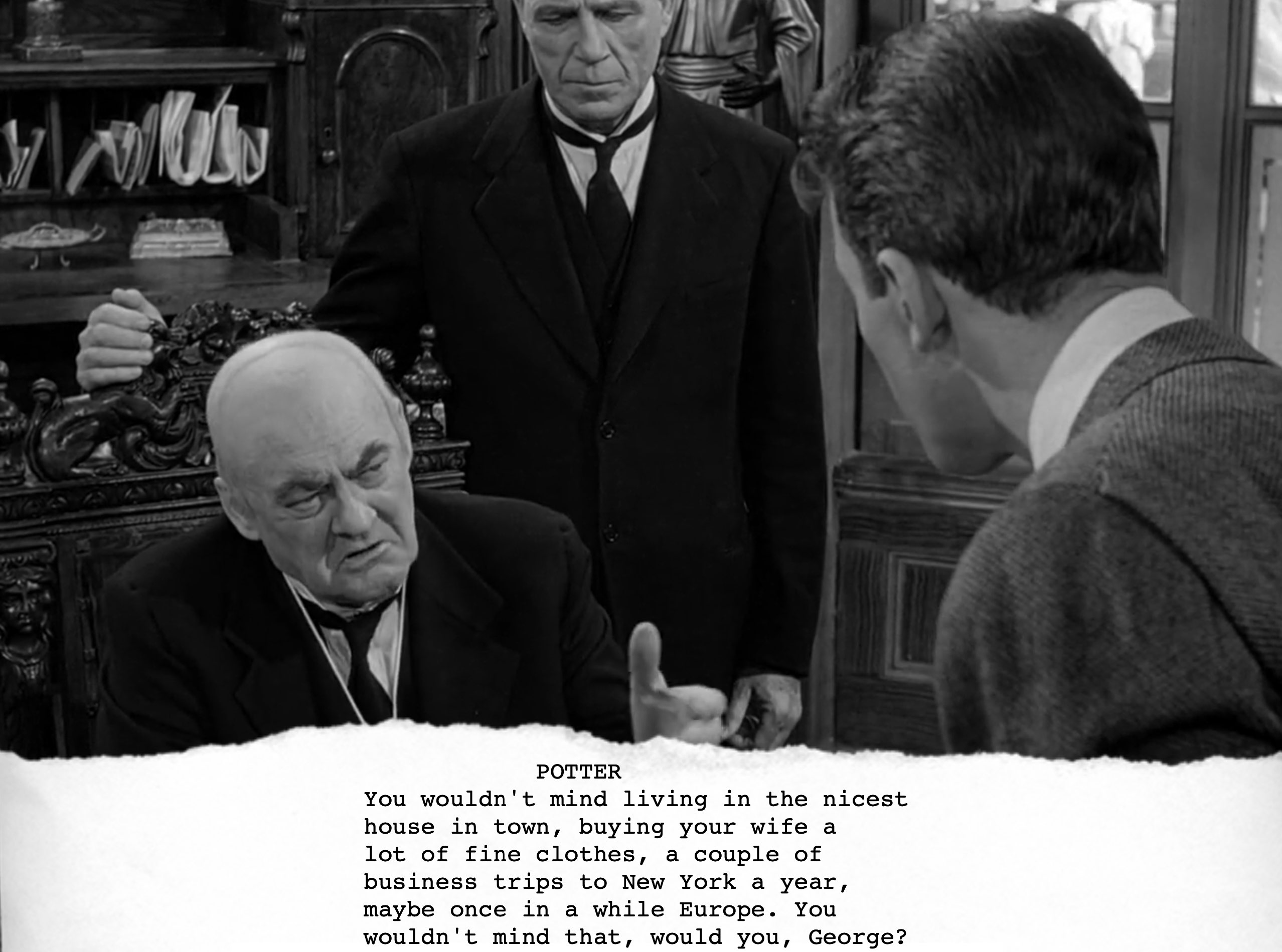

At this point, things are pretty much settled. There’s only one further opportunity for travel, and that comes soon after when Mr Potter offers George employment. It’s a job, Potter tells him, that just happens to involve a lot of travel.

You can see the desire wash over George. This bonus almost sways him. New York? Europe? He’s tempted, but ultimately resists. And he does this on his own.

…except Mary has a contingency plan. When he stumbles home after turning down Potter’s offer, thoughts spinning in his head, likely filled with regret and reconsidering his decision, Mary is ready. She’s got the nuclear option locked and loaded. She tells him she’s pregnant.

This is a risky plan: he could easily hear that and think well, now I have to provide for my family, even if it means swallowing my pride and crawling back to Potter. But Mary knows him too well. She knows full well George will not travel when the mother of his children is stuck at home with their newborn, and she also knows George knows his father was perfectly equipped to raise a family on a Building and Loan salary. She’s got this sorted.

But in for a penny, in for a pound, and she pumps out a few more. Over the course of a quick montage, she gets the brood up to four, just to be sure. There is no chance for George now. He’s never getting out of town.

The Broken Window

“But, Lee!” I hear you cry. “Don’t think we didn’t notice that you left one out. The very first chance George has to leave is the scene in which we’re introduced to Jimmy Stewart as the Adult George: he’s bought his suitcase! He’s got his ticket! He’s getting ready to leave, and only stays because – in the wake of his father’s death – the board will dissolve the Building and Loan unless he personally stays on to run it. You’re saying Mary was somehow responsible for that?”

That is exactly what I’m saying.

Again, you can put the blame on George’s own sense of right, or blame the board, or blame Mr Potter, who is pulling all the strings in plain sight. But all these actions are predictable; the only unpredictable act is Peter Bailey having a sudden, unexpected stroke.

Now think back to George and Mary, walking back from the graduation party in whatever rags George could spirit out of the locker room, promising to lasso the moon and throwing rocks at the old Granville house.

You throw a stone, you break a window, you make a wish. For George, it’s a childhood game, and nothing to be taken seriously. But still he talks of his desire to leave this crummy town to see the world, and suddenly there’s a look of absolute determination on Mary’s face. Of focus. Of resolve. Something is happening there, and when she throws her stone with unerring accuracy and hits that window like a bullseye, she goes hard on her wish. You know it’s serious.

George wants to know what she wished for, but she won’t say. She can’t.

And what happens exactly three minutes later? A car pulls up to tell George the news: his father has just had a stroke.

I’m not proposing Mary wished explicitly for Pa Bailey to be struck down, but she clearly wished George would stay in Bedford Falls – she practically admits as much on their wedding night – and there was only one thing that could have kept him there. The cosmos has a habit of punishing us by granting our wishes.

Mary feels guilty. Of course she does. There’s a reason their courtship is put on ice for three years, and it’s not just because she’s gone away to some school we never hear anything about ever again. But it’s in that exact moment that she appreciates the forces she has at her command, the power she has to manipulate events.

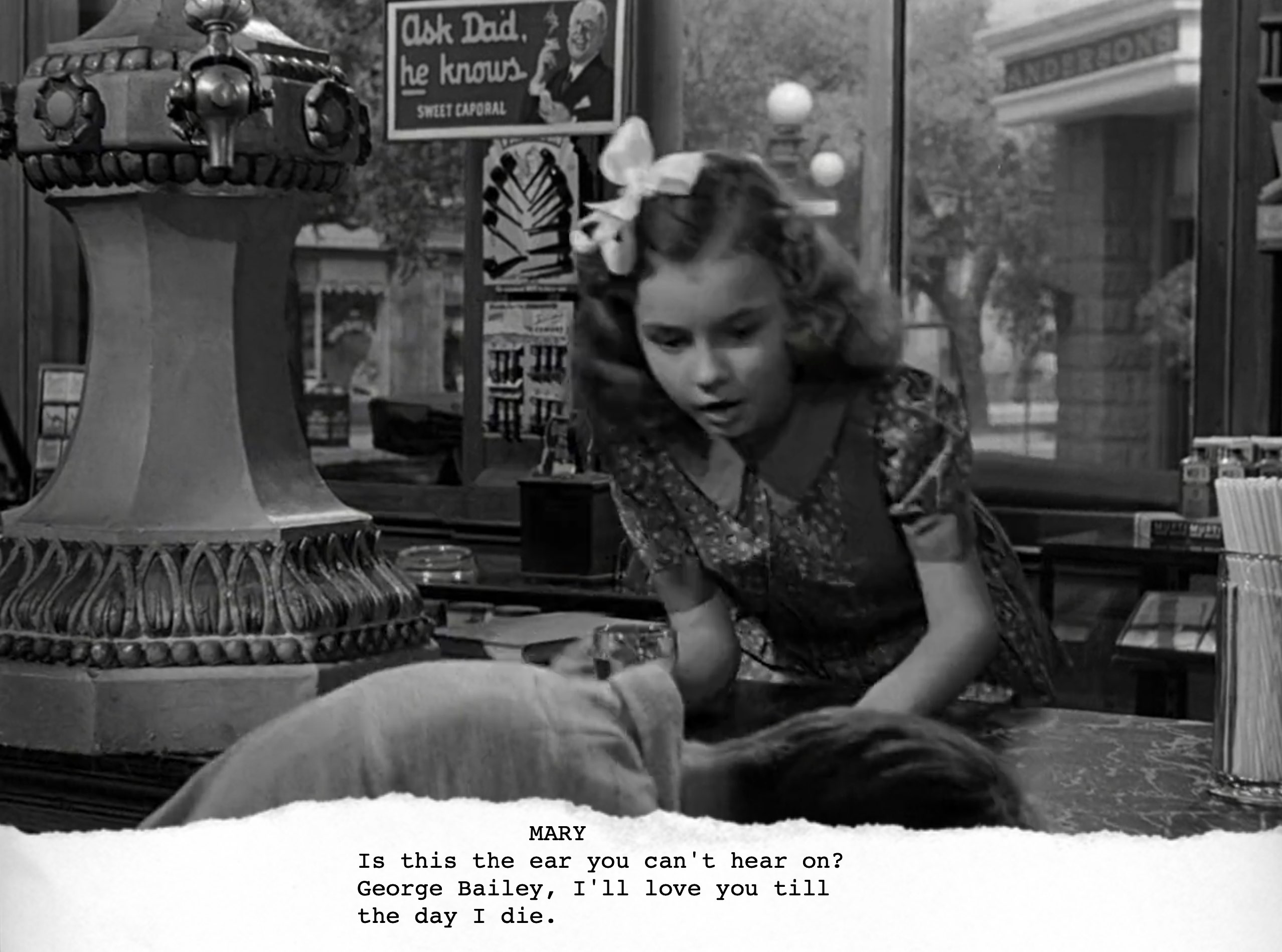

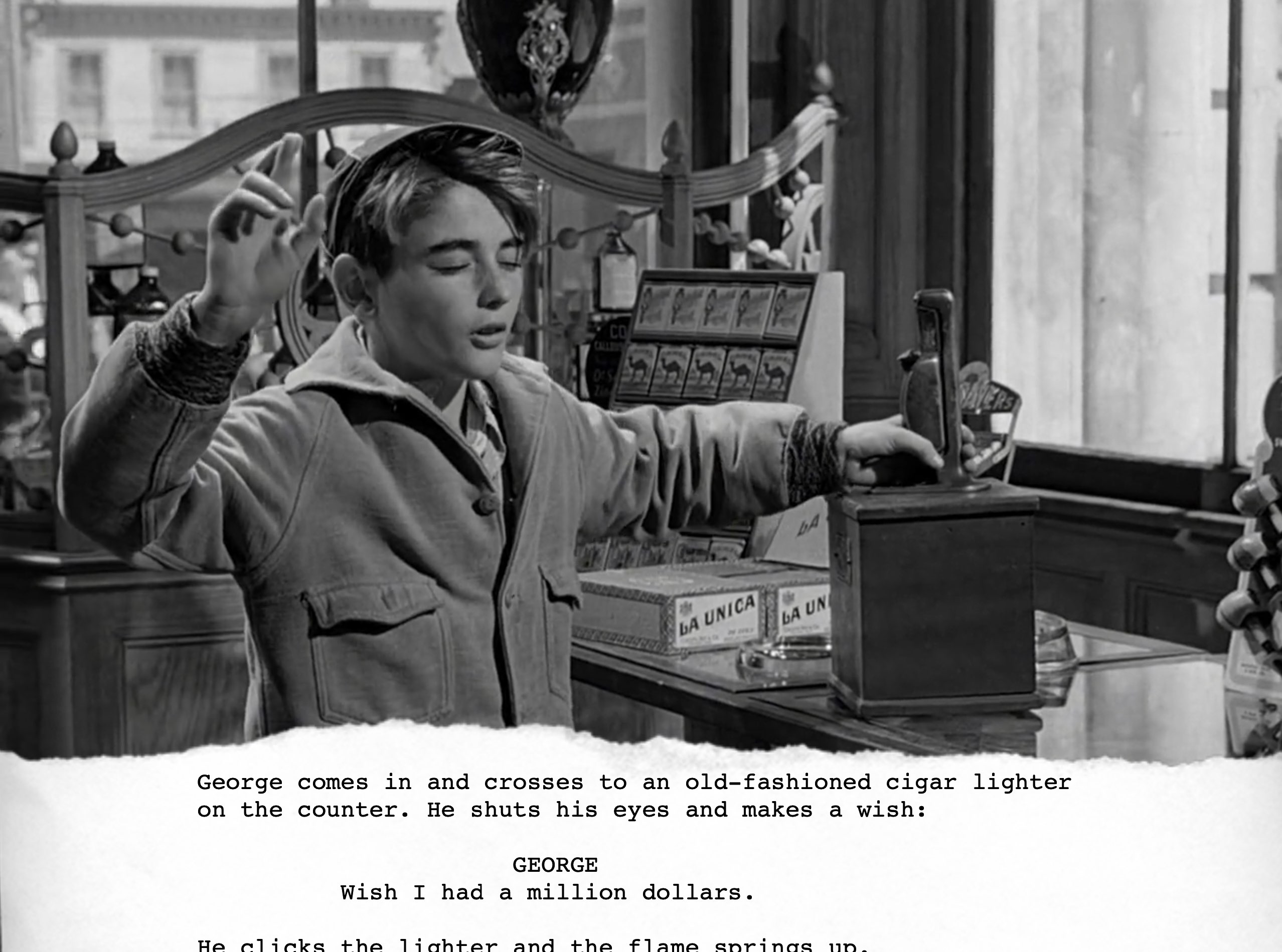

Ever since the moment years earlier in the drugstore when the Child George boasts he’s been nominated for membership in the National Geographic Society, and Child Mary leans into his deaf ear and counters his dreams with a declaration of love – whispered like the villain who can’t help but reveal her plans to the hero, in retrospect a threat more than a promise – she has been hellbent on her ambition of foiling his true desire at every turn.

There is no bigger villain in Bedford Falls than Mary.

Unless…

Unless she was actually doing it for unselfish reasons.

Unless Mary has a grander purpose in mind.

Unless she was operating at a level nobody could possibly comprehend.

Unless there is something else entirely going on.

MARY IS THE HERO OF BEDFORD FALLS

At this point, we’ve established Mary as a Machiavellian figure who sees every angle and manipulates every possibility.

So surely someone with the kind of insight Mary possesses would be able to see how close Bedford Falls is to calamity. How precariously it teeters on the cliff’s edge, just one bad day from descending into a hedonistic nightmare, monopolised by the greedy and unscrupulous Mr Potter.

What if Mary knows full well that the only thing preventing Bedford Falls from becoming Pottersville is a man named George Bailey?

After all, her ongoing plan to keep George firmly rooted in Bedford Falls doesn’t really make sense from any other angle. At first it may seem like she’s keeping him there so he won’t run away from her, but once they’re married why does she continue to thwart him? At that point, anywhere he goes, she’s going with him.

Her actions only make sense if she’s doing it for a whole other reason.

Keeping George in Bedford Falls is crucial to saving everybody: without him, Ma Bailey becomes bitter and twisted, Uncle Billy’s in the insane asylum, Ernie’s wife runs off, Violet’s arrested, Mr Gower is a child-killing drunk, and the town turns into a sleazy, slum-filled hellscape.

Maybe Mary has to be the villain of George’s life in order to be the hero of everyone else’s.

And maybe she knows how to convene cosmic forces in order to keep things that way.

Now think about this: who exactly is it that summons Clarence the guardian angel?

It happens in the opening moments of the film, hiding in plain sight. The prayers of the town, ending with one house: the Old Granville House, where the voice of Mary and her two daughters call out to the stars. To the angel that will save George from doing the unthinkable.

And suddenly, everything Mary does that evening makes sense.

Because when George stumbles out into the night, Mary does not go looking for him. She doesn’t even alert anyone that his life might be in danger. What does she do? She apparently goes around telling everyone that he is in financial trouble.

Why?

It’s clear from his erratic behaviour that something is wrong with him on a deeply dangerous level, so why is she concerned with raising money instead of his immediate safety? Why does she leave her children at home and head out into the snow unless she knows the money is what’s needed to make George stay? Unless she knows there’s a guardian angel who can save him from taking the plunge off that bridge?

As a child, Mary watched as George wished for a million dollars.

She was the one who heard his prayer that day. And while she doesn’t quite raise the full million, she is the one who provides him with money when he needs it the most. And not for the first time.

Mary is the true hero of Bedford Falls.

But all that still leaves one final question: why?

Why has it fallen to this woman to save the town?

Why is Mary so altruistic?

At this point, I’m going to say that if you’re not ready to know the truth about Bedford Falls, you should stop reading here. After all, we’ve reached a nice resolution. Mary is a hero. This is a good place to leave it. Maybe now’s the time to pull the ripcord. Maybe it’s best you don’t go on.

Because it turns out Mary’s motives might be coming from a very different place.

A place with an entirely different name.

MARY IS THE VILLAIN OF POTTERSVILLE

Pottersville isn’t the alternate reality.

Bedford Falls is.

Consider everything we know about the world you and I inhabit. Which of the two realities presented in the film seems plausible and which seems fanciful? If you were shown these two towns – the Norman Rockwell painting of “aw shucks” nobility and drugstore malts, or the siren-blaring home of sadistic barkeeps and trigger-happy cops – and were asked which hewed closer to reality, you’d be pushing all your chips in on Pottersville.

Now imagine a woman living in Pottersville, a librarian who hates her life and hates her town. The horror she sees around her is a world away from the fantasies of the books she consumes. Her whole life has been haunted by the memory a child named Harry Bailey, just a few years younger than her, who drowned in an ice lake. Isn’t it plausible that this woman would wish for a hero? An older brother to the drowned child who could have saved him in the nick of time, and then gone on to save everyone else.

Imagine a child so innately gifted, strong-willed and moral, he could confront the town’s wealthy tycoon bully, prevent the accidental poisoning of a child, and provide an emotional breakthrough for his grieving employer, all in the space of about 15 minutes on a work day.

Someone who could keep the fabric of the town together.

Someone named George.

And she wished for this perfect exemplar of a man, wished so hard she managed to create a whole new reality. One she had to work very, very hard to maintain. Because if her invention ever steps outside of city limits, all of it comes crumbling down around her.

Then, one day, her invention began to slip away. George was so busy keeping everyone else together, he lost all hope for himself. What could she possibly do to save him? What power could be higher than the unimpeachable George Bailey? No one on Earth, that’s for sure. And that means looking to the heavens.

It means receiving the help of an angel, summoned not just by Mary, but her daughters, the daughters who should never exist. Innocent prayers of a reality that should never have been. Shouldn’t Clarence see this? Maybe not. He’s yet to earn his wings, and in the opening we establish he literally cannot see any reality before him without assistance. He simply doesn’t have the power.

(As an aside: why doesn’t Joseph, or the other heavenly voice, notice? It could be that they’re simply not paying enough attention; after all, this problem is so far down on their priority list, they’ve palmed it off to Heaven’s waterboy. Or maybe that is the test. Maybe discerning realities is what will actually earn Clarence his wings.)

When George wishes he had never been born, are we meant to believe that Clarence Odbody can suddenly make that happen? Clarence, who keeps failing to earn his wings, who can’t see anything in front of him without assistance, who can’t even evade a taxi driver without calling for help from Joseph… this guy can suddenly alter the timelines? Reshape the world into an alternate reality? How could that be, unless that alternate reality was actually the primary one, waiting for the smallest trigger to be restored?

How could Clarence manage this unless Pottersville is the real world?

And now, much of what happens during the Pottersville sojourn makes sense.

“I’m not supposed to tell!” protests Clarence, as George demands to know where Mary is. Why not? He hasn’t been shy about every other piece of information. Why would he be afraid to tell George this? On whose orders is he acting?

“She’s an old maid!” he reveals, screaming that she’s just about to lock up the public library. Is that something an angel would get so worked up about? Is that a fact he would think was tantamount the end of the world, or is that something he’d only reveal if he was starting to figure out what was actually going on? If he was starting to work out the real game?

Where exactly does Clarence go when he disappears? Where is he when George visits Ma Bailey’s boarding house? Why is he suddenly afraid of revealing simple information? Why is he suddenly afraid of talking about Mary?

Late at night, Mary Hatch finds herself back at the library. Reality has reshaped around her. How much does she know? Is she aware that her tenuous plan finally stretched too far and reality has snapped back? Or does she think she’s awoken from an impossible dream of old houses and air raids and apple-cheeked children? She shakes it off and locks up the library. And she’s confronted by a stranger.

But he’s not a stranger. Look at the expression her face when she first encounters George. That is a look of horrific recognition. That is the look of someone whose dream has suddenly materialised before her.

She breaks free and moves away from him quickly, unable to believe that this is happening. No matter what she thinks the situation is, George simply should not be here. He cannot.

George follows her. Looking like a crazed madman, stumbling about like the Pottersville iteration of her perfect man, he runs after her into the Blue Moon Bar, crying out that Mary is his wife. It’s too much. She screams, then faints.

But why would she faint? She’s grown up in the hellhole that is Pottersville, one clearly replete with all kinds of nefarious and demented figures; there’s no way something like this would faze her. The only way she would react in such a dramatic fashion is if she was watching her fantasy suddenly coming to life and appearing before her. That is what’s too much to bear.

Mary collapses. Time and reality have folded in on themselves. The lines have been blurred, and it’s no longer clear which reality has spawned which. Causality is twisted.

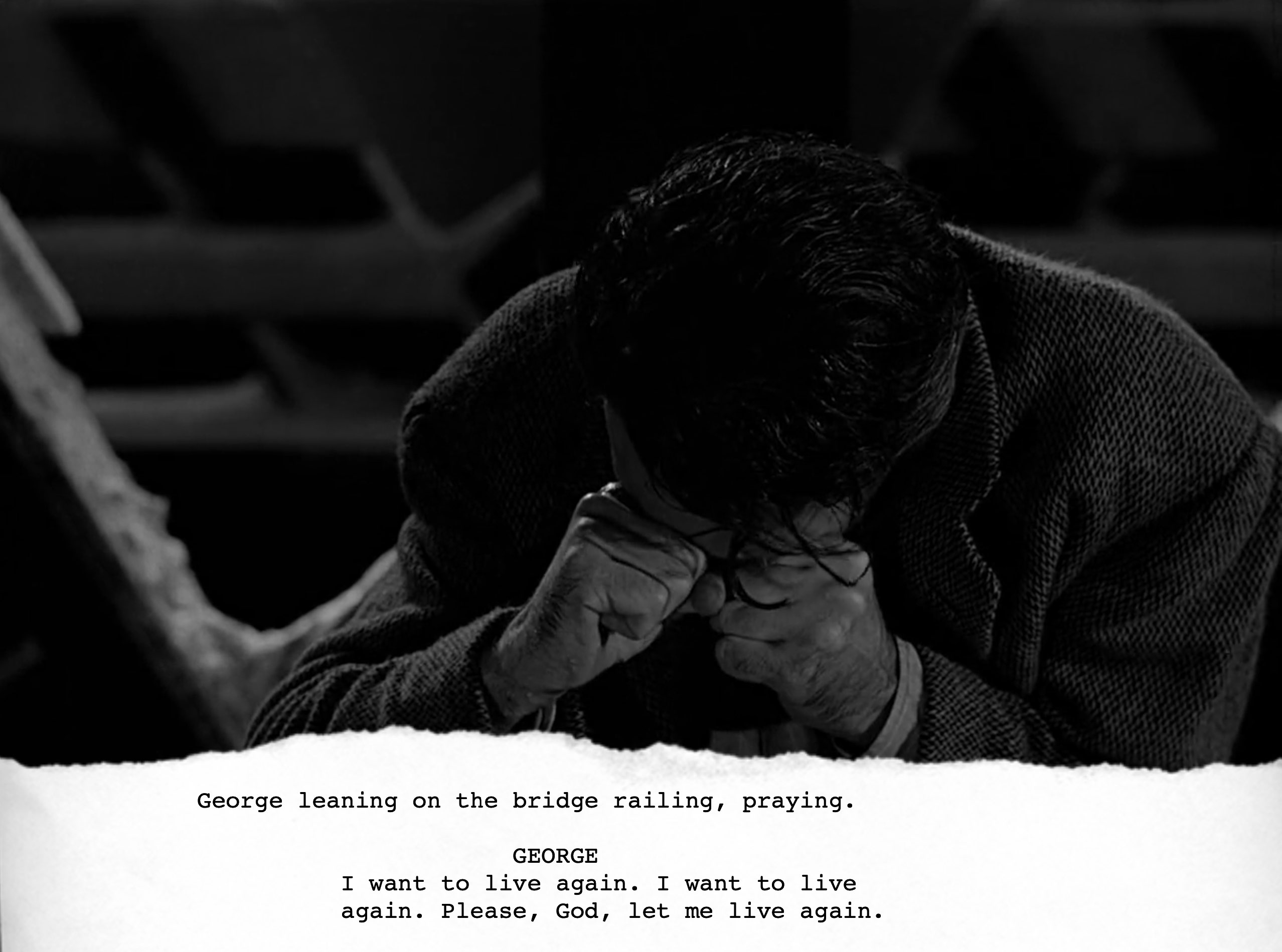

But she’s done just enough to make it stick. Mary Hatch, the old maid librarian of Pottersville, has crafted a reality so strong, it wants to live. It yearns to. Back on the bridge, George’s plaintive pleas betray the true journey George has gone on. He knows full well he does not exist. He knows he is a figment.

This is a man who wants to be made flesh.

Mary rushes back into the house. Maybe she really was out collecting the emergency money, or maybe she was actually trapped in the other reality, physically crossing between worlds while others lived in ignorance as they reformed around her. Maybe when she re-enters at the end, she’s just returned from the Pottersville Library and the Blue Moon Bar, and after a quick change of clothing walks in through the front door of the Old Granville House, the one she and her creation once pitched rocks at.

And now she’s back. To the husband she literally dreamed of, to the house she always wanted, to the perfect life she forced into being.

As the money rolls in, Mary is ecstatic; more so than George, because she knows what it really means.

She knows it will keep him from ever leaving Bedford Falls, it will stop Potter from consolidating his hold over the town, it will keep her from a life of loneliness and solitude, and it will keep the cruel world she once knew from ever returning.

It doesn’t matter that this is a story about choices, and that she single-handedly declared the choice of everyone in her home town to be wrong and in need of correction. It doesn’t matter that in robbing them of agency, she is the greatest villain Pottersville has ever known.

What matters is who is the real villain of Bedford Falls. And that question is moot. Because Bedford Falls never existed.

this was a suuuuper fun read!