It’s possible I watched too many films this year. I’m really not sure how I managed that, given there were no enforced lockdowns and I left the house quite a bit. Yet somehow, I came pretty close to watching the same number of films as I did in both 2020 and 2021 combined.

A lot of that might be due to Paul Anthony Nelson roping me into bespoke games of Screen Drafts. You don’t need to know what that is; the only relevant information is that I have an obsessive personality and spent most of the year watching almost every film released in 1982, 1979 and 1976. (I am, by the way, now absolutely convinced there is no better way to engage with cinema. Forget focussing on a genre, following sequels, completing directorial canons: just pick a calendar year and go nuts. It’s revelatory.)

Speaking of older films, I did field a request to start adding my best first-time retro watches to this round-up. The discovers that hit me hardest included (in no particular order): Contempt (1963), Do the Right Thing (1989), Siberiade (1979), In Bruges (2008), Cinema Paradiso (1988), Fanny and Alexander (1982), Small Change (1976), The Marquise of O (1976), The 400 Blows (1959), The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982), Alexandria… Why? (1979), Fantasia 2000 (1999), Christ Stopped At Eboli (1979), and Insiang (1976).

Those release dates are only slightly more eclectic than my 2022 list, which is all over the shop in a way that drives some of my film crit friends mad. (“Film Critics Hate Him Because Of This One Weird Trick”) I’ve long-since given up being evangelical about release dates, so the below is a mishmash of 2022 releases, 2021 releases held over in Australia (as well as one from 2020), and 2023 titles I somehow managed to catch early. So essentially, my favourite films of the year spans four years. I wouldn’t worry about it too much. If art can be subjective, why can’t time?

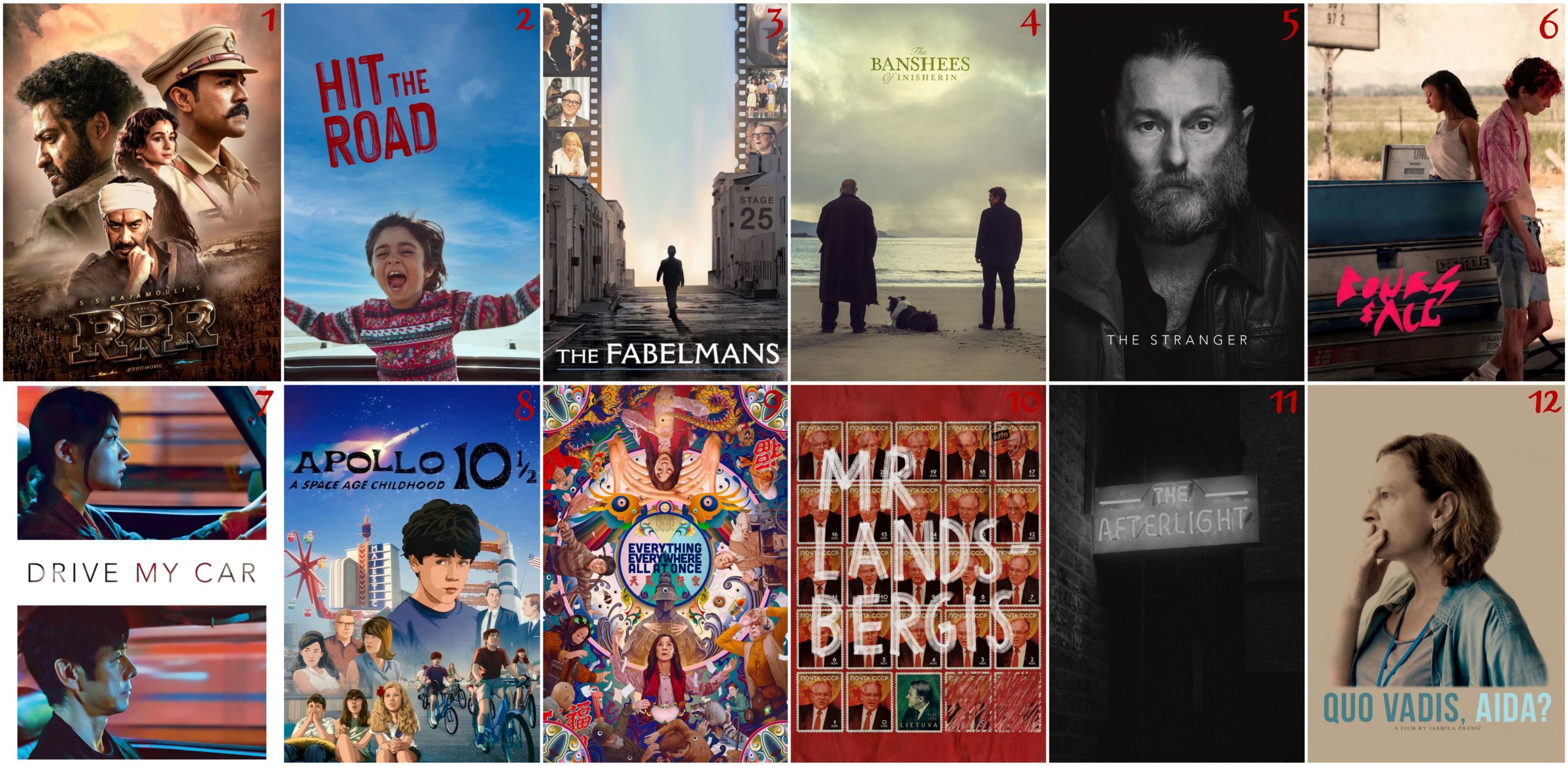

This year, I’ve again opted for 12 top films instead of the trad 10, just down to the fact that there were 12 films I adored. Actually, there were heaps more than that, and I could very happily have made a parallel list containing Pedro Almodóvar’s Parallel Mothers, Claire Denis’s Stars at Noon, David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future, Sophie Hyde’s Good Luck To You, Leo Grande, Del Kathryn Barton’s Blaze, Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s Man on Earth, Park Chan-Wook’s Decision To Leave, Ruben Östland’s Triangle of Sadness, Mike Mills’s C’Mon C’Mon, George Miller’s Three Thousand Years of Longing, Céline Sciamma’s Petite Maman, Colm Bairéad’s The Quiet Girl, Lena Dunham’s Catherine Called Birdy, Goran Stolevski’s You Won’t Be Alone, Hirokazu Koreeda’s Broker, and Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee. I was even tempted to include the schlocky horror film Fall for the simple and ingenious way it executed its premise. But also so I could make a joke about elevated horror.

So which films could possibly beat out that deep bench of all-stars? Let’s find out. Together.

12. Quo Vadis, Aida?

12. Quo Vadis, Aida?

There are few concepts more incisive than Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil”, one of the few phrases of modern philosophy that is actually served well by endless repetition. Like it’s a magic spell holding back the lionisation of absurd crypto-fascists who are one fortuitous day away from that prefix fading into redundancy. In other words: history’s greatest monsters aren’t the moustache-twirling supervillains we’d like to believe, but dull men as ordinary as anyone you’d pass in the street. Arendt’s concept – one you’d think crucial to any depiction of the horrors of war – has really never been rendered in film as effectively as in Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida?, about the 1995 Srebrenica massacre. Told from the perspective of a United Nations translator, the piercing film shows just how pedestrian the small moments of officious contempt can be, those trivial decisions that that soon turn into existential horror, a domino effect it depicts with absolute realism. Realism here is not a shaky camera, a desaturated image, or a lack of music score; Žbanić is not above embracing many conventional tools of filmmaking, like restrained flashbacks or slow-motion. The realism comes in the unerring authenticity of human nature. Every interaction. Every negotiation. Every shift of power. Every single decision rooted in something horribly familiar. It’s why this film (and, y’know, the medium of cinema in general) is so powerful: we can read a hundred headlines on a massacre, but until we see it dramatised, we can never truly feel the weight of it. But noble intent doesn’t necessarily make for great cinema. Even divorced from historical context, this was one of the most compelling, remarkable films I saw all year. Writer/director Žbanić makes the precise right choice at every turn, knowing when to pull back and when to push in, demonstrating a restraint and balance that I suspect most other filmmakers would struggle with. Star Jasna Đuričić anchors the film with an urgent, desperate performance, and the final sequence – somehow understated and florid all at once – cements this film as one for the ages. Of course, Žbanić clearly wouldn’t have set out to make “one for the ages”, which is rather the point. Far too many historical works are consumed with the comical idea that the actions of people in the past were dictated by the weight of time, that they already have their eye on their place in history, aware of us gazing back at them. It is extraordinary to see a film depicting an important historical event in which people are simply trying to survive each moment. And in seeing that, all of history suddenly makes perfect, horrific sense.

11. The Afterlight

11. The Afterlight

In 2017, everyone’s favourite eccentric Winnipeg filmmaker Guy Maddin released The Green Fog, a film he co-directed with brothers Evan and Galen Johnson, constructed almost entirely of clips from films and TV shows either set or filmed in San Francisco. The result blended everything from Dirty Harry to Mrs Doubtfire in an attempt to create a narrative of its own, emulating the ultimate San Franciscan film (Hitchcock’s Vertigo) through archive footage. It is, frankly, a work of genius, but one that is – due to the nature of its construction and the tangled web of intellectual property and clearance rights – unlikely to ever see a commercial release. There’s a strange appeal in that; the films that can only ever exist in the moment in which you see them. That’s certainly the case with The Afterlight, in which director Charlie Shackleton looks to The Green Fog and says: “Hold my clip of a beer from this long-lost 1928 film.” Shackleton’s crafted something that is in many ways more experimental, pasting together fragmented clips of actors who all share one common trait: they are no longer alive. There is something deliberately haunting about the moments Shackleton finds, the absolute antithesis of those big trailer moments where someone pulls a punctuative expression or executes a compelling motion. These are the small gestures of people at ease in their skin, and they are stitched in a way that does not create a narrative so much as a continuity of movement. The film begins with characters walking across empty environs, the sound of their footsteps echoing through the tranquillity of the past. It’s hypnotic. Eventually, they make it to a watering hole – a crafty edit suggests they are all in a bar named The Afterlight, the only element shot especially for the film – and the audio mix places them in adjacent rooms, each in their own world as people come and go and fight and despair. This is the tone the film strikes throughout, as we move across new locales; American, British, Japanese, German actors all demonstrating commonality through the mundane act of existing, from trying to escape the rain or drinking to the point of regret. But underpinning that is the constant reminder that everyone we are seeing only now exists in this literal afterlight. And that mortality is entwined in the medium, because, crucially, the film itself is fragile and rare: according to the director, only one copy of the thing exists. There’s a single 35mm print that travels with Shackleton from festival to festival. There is no negative, no stored copy on a hard drive somewhere. The archivist in me shivers, but the idea that this film only exists as a mortal, physical object itself makes the experience of viewing it all the more profound, in ways you can’t quite imagine until it begins. It’s not the first time I’ve seen a film whereby, should the literal physical copy you are watching disappear or break, it will be gone forever. In an age of infinite accessibility, knowing that this work will one day decay along with all life is as melancholy as it is beautiful.

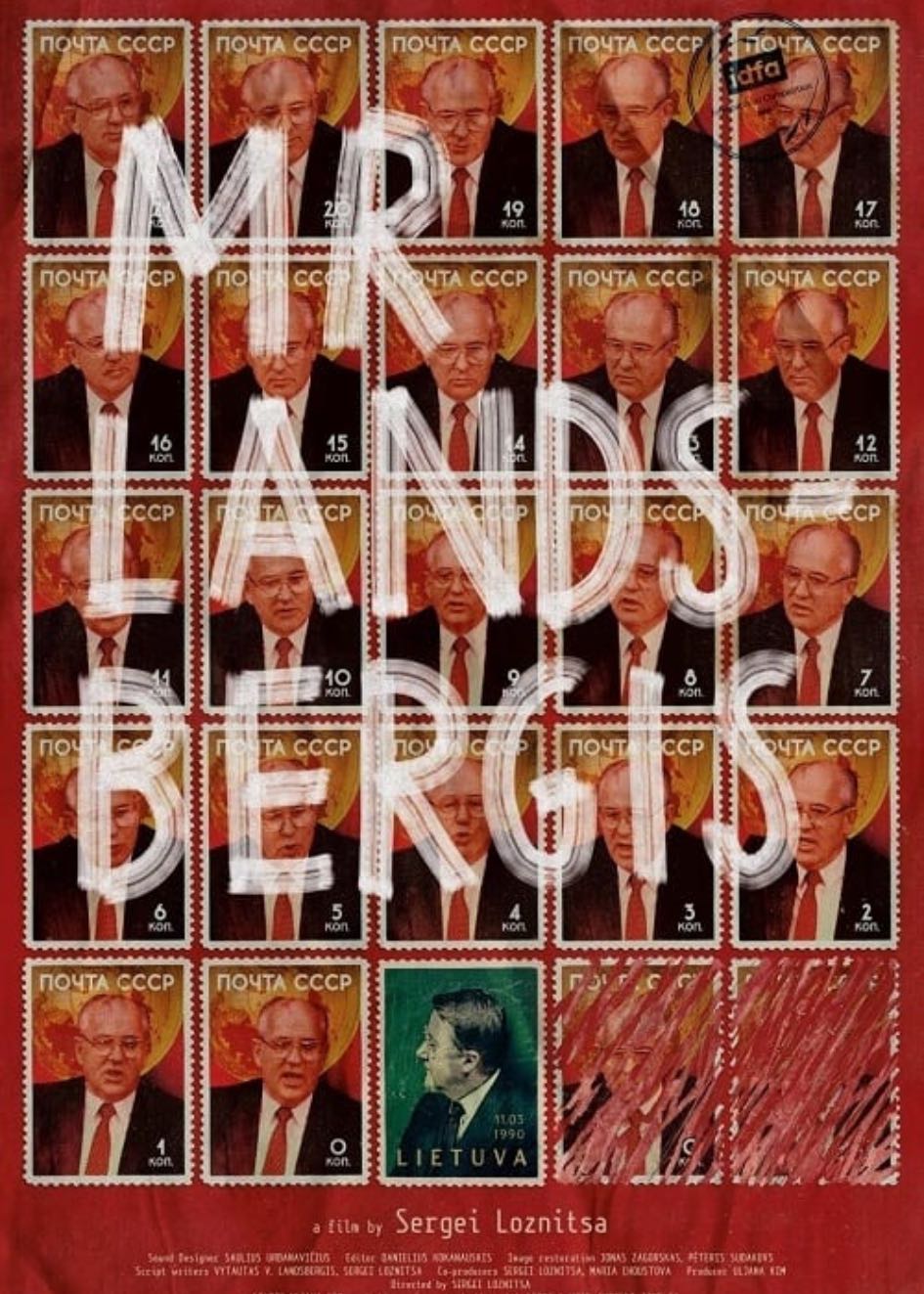

10. Mr Landsbergis

10. Mr Landsbergis

At some point during this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival, I realised I’d have to make a difficult choice: I could either continue my ongoing quest to convince civilians that film festivals are actually fun, vibrant events filled with an eclectic mix of exciting titles, instead of the bleak, interminable overly-long foreign-language documentaries everyone assumes… or I could admit that the best time I had in a cinema this festival was a four-hour documentary about Lithuanian independence. I’m still debating which way to go. Filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa – who seems to hold a permanent reservation in my end-of-year lists – continues his streak as the most innately-gifted documentary filmmaker working today with a film that breaks a key tradition of his own canon. Like many of his previous works, Mr Landsbergis is fundamentally about a reckoning with liberty, depicted with the type of rare, remarkable archive footage you can’t believe has just been sitting in a vault somewhere – and it’s damning that so much is so available and so rarely used. But the film also features another rarity: a modern framing device. Loznitsa sits down with Vytautas Landsbergis, one of the figures at the vanguard of the Lithuania’s freedom movement and the man for whom the film is named, and allows him a present-day contextualising of the events that led to the country breaking from the Soviet bloc. It feels like Loznitsa is breaking some unspoken rule in allowing such a reminiscence, but it’s crucial context. That present-day lens has always been inescapable, given the act of selecting the archive footage is done with a modern eye. It’s why the shadow of Ukraine’s current struggle looms large over this work, deliberately or not, adding fresh urgency to this document. Its defiant four-hour running time breezes past, as every small moment and detail transports us back to an incredible and long-lost moment in time.

9. Everything, Everywhere, All At Once

9. Everything, Everywhere, All At Once

This should not have worked for me at all. On the face of it, it does something that often turns me off films on an almost genetic level: it furiously maintains an unrelenting pace. It finds a high gear and seems content to stay in it for almost two-and-a-half hours, in a way that I normally find exhausting and amateurishly antithetical to the natural flow of storytelling. So why is Everything, Everywhere, All At Once not just an exception to the rule, but exceptional enough to elbow its way into my heart? It’s because filmmakers Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert have made a film about the relentlessness of life, an idea that would work perfectly well in the abstract, but absolutely sings when delivered on a visceral level. Life rarely gives you space to breathe and rest, so why should this? While many films with this kind of desperate, kinetic energy use the momentum to distract from the emptiness of its calories, this one artfully directs it into a universally-relatable story of choices and regret and acceptance. Multiverse stories have, on some level, always been about the choices not taken, but until recently the concept has mostly been the domain of cult science fiction. Humanity now seems to be entering a uniquely existential epoch, and so the concept of parallel realities has – after a number of false starts – finally pierced the mainstream. I wonder if that kind of wider acceptance is what allowed a film like this to take such big narrative risks, swinging wildly at impossible ideas and ludicrous visuals, all while never losing sight of the very human emotion that drives it. That emotion is flawlessly embodied by the great Michelle Yeoh, in an absolute gift of a performance. It’s a flavour of big budget fantasy so rarely seen: cartoonishly frenetic one moment, and deeply heartfelt the next.

8. Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood

8. Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood

Nostalgia has got a bad rap, in part because of the bad faith manner in which it’s politically weaponised, but also because it is seen (not always incorrectly) as the manifestation of arrested cultural development. You can’t look to the future if you’re fixated on the past. But nostalgia is also a way of processing history, and there’s no one-size-fits all approach to the backwards gaze; in many ways, the rose-coloured appreciation of a happy past feels healthy. In Apollo 10½, Richard Linklater again employs the rotoscope animation he used in Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly to tell the story of his own childhood, and the undoubtedly-factual story of how he was recruited by NASA during the fourth grade to fly a secret mission to the moon. The story is far more about growing up in the summer of ’69 than the astronaut fantasy, and Linklater wisely uses the framing device sparingly. So many of his films have tried to capture a certain magic of childhood, and it’s interesting that this – his most successful attempt – has discarded almost all narrative pretence (space-faring moments aside) and just simply taken us there. The film is drunk on its own wistfulness, and for anyone who’s ever wanted to live in the slow moody in-between moments of a movie and impractically wished those scenes could go on forever – like the cretins who ask why the entire plane isn’t made out of the black box material – the wish is now granted. I’ve written in the past about the special type of nostalgic filmmaking that, at its best, leaves you certain that you grew up in the time and place depicted. Last year, Paolo Sorrentino’s The Hand of God had me convinced my childhood had taken place in 1980s Naples. Thanks to Richard Linklater, I am now also a child of 1970s Houston.

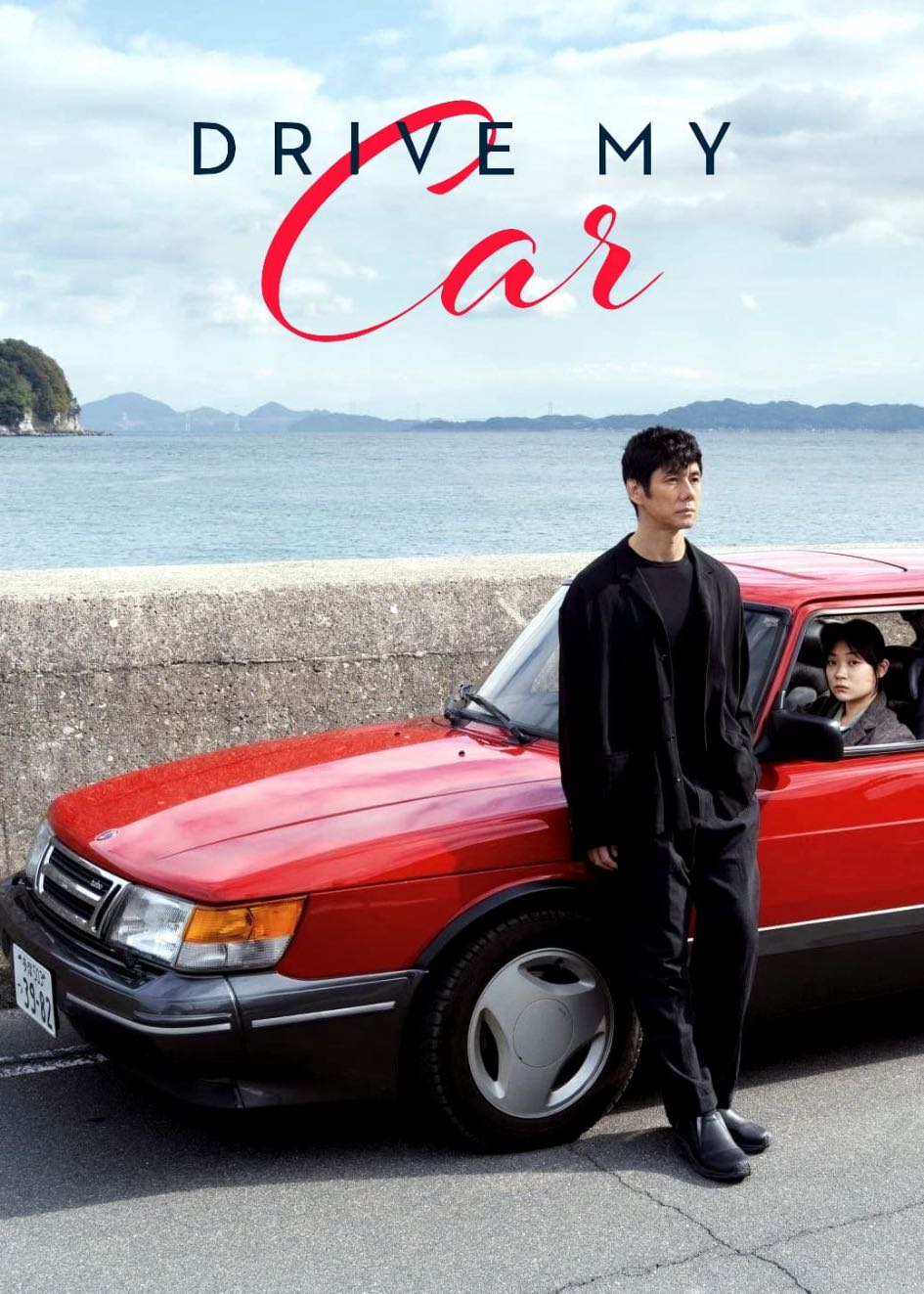

7. Drive My Car

7. Drive My Car

The idea that art has the ability to transcend language seems, at first, to be at the heart of the Uncle Vanyaproduction that binds the characters in Drive My Car: a Russian play, directed in Japanese, performed in Indonesian, Malaysian, German, as well as Korean sign language. But director Yusuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is not trying to transcend anything. If anything, he’s throwing up as many barriers as possible to shield himself from the pain of communication. He does not want to talk. The reluctance to communicate is hardly fresh terrain for cinema, but it’s impossible to recall an instance in which the subject has been handled as gently as it is here. Like the solving of a mystery, we trace the lines throughout Yusuke’s life, from the inciting trauma that led to the exclusively post-coital storytelling sessions with his wife, to the infidelities that betray that ritual more than the marriage itself, right through to the recorded voice that haunts the car speakers, heard by both the widowed husband and the driver he is reluctant to engage with. Silence echoes, and for a man whose job is to communicate – to his actors and, through them, to an audience – that silence is as much comforting as it is damaging. Yusuke is often inscrutable, but Drive My Car is not, perhaps the most intimate and graceful film I saw all year.

6. Bones and All

6. Bones and All

There are many filmmakers, all of them beloved by cinematic cultists, who explore the sensual via the grotesque, doing so with enigmatic divinity or lurid voyeurism. Luca Guadagnino seems to approach it with an earnest curiosity that feels almost naïve. How many other filmmakers could exercise the restraint necessary to hold back anything explicitly sexual between the two leads? The film is practically begging for the release, but to give into that temptation would rob the cannibalism – a fairly crucial element of the film, curiously absent from much of the marketing – of its power: in this film, eating human flesh is sex. To keep the latter in the domain of the former is the most romantic move the film could make, executed in a discreet way rare for modern cinema. Bones and All reels from the subtle to the overt, and both modes are welcome. For all the contempt directed at films that spell their ideas out in big letters, how many of our favourite moments come from filmmakers putting it all out on Front Street? Guadagnino’s film is lyrical and passionate, as much Interview with the Vampire as My Own Private Idaho, a road trip and gothic horror and tragic romance in one, proudly carrying the torch for the grand tradition of monster movies that dangerously dance on the delicate line between sex and violence.

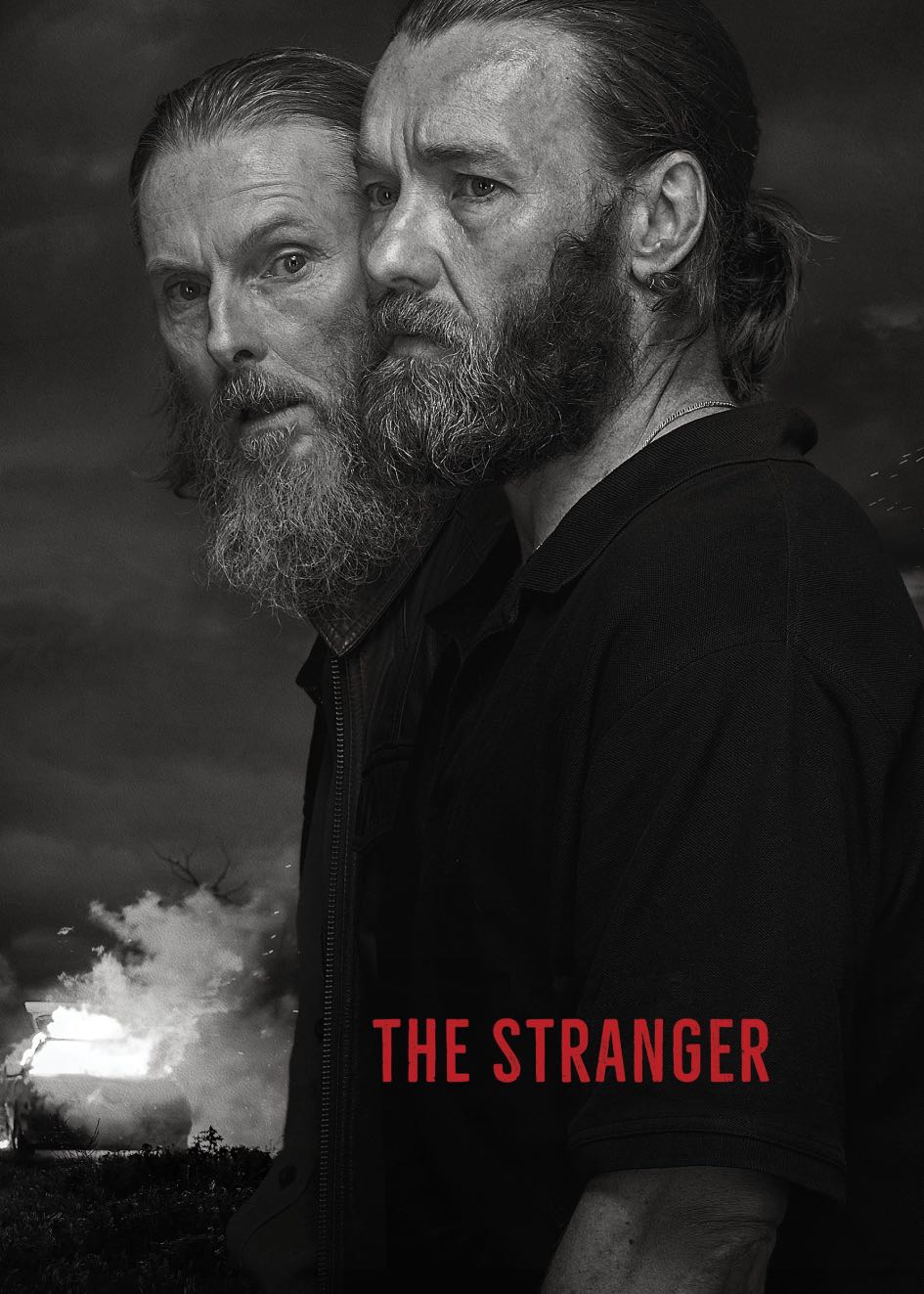

5. The Stranger

5. The Stranger

It was the shot of tail lights in the darkness that shook me from my stupor. I had fallen sick the night I watched The Stranger, and the film played like a dream, a mass of noise and shape that was hypnotic and captivating. Then suddenly, there it was: the rear lights of a car, an Australian numberplate, seen through a windscreen, the driver on the right, all before a green-and-white sign at a remote intersection like hundreds I’ve seen before. The dream had been interrupted by reality; in some ways, the most mundane shot in the film, but so brutally tactile, it forced me into The Stranger’s world in a way no immersive IMAX experience could ever hope to replicate. It’s that mix of real and surreal, the factual and the mythic, that makes The Stranger so arresting. In every sense of the word. The Daniel Morcombe disappearance is still relatively fresh in the memory, and to see it dramatised in such an illusory manner is deeply unsettling, and not in a bad way. We should be unsettled. The film is both rooted in reality and lost in a dreamscape, an stylistic approach that seems respectful to the unimaginable crime at the heart of it. Thomas M Wright’s film is every inch a masterpiece, one of the most horrifying visions of Australia since Ted Kotcheff’s Wake In Fright. It is a tightly-coiled threat of a film, where danger seethes under the surface, one small scratch away exploding.

4. The Banshees of Inisherin

4. The Banshees of Inisherin

“In the particular is contained the universal,” said James Joyce, and it’s difficult not to see the DNA of Ireland’s Greatest Writer woven throughout Martin McDonagh’s Banshees. It doesn’t take a lot of effort to imagine the inhabitants of Inisherin transposed into the pages of Finnigans Wake, where a simple misunderstanding can butterfly effect its way chaotically across Dublin. In the case of Banshees, Joyce’s particular is a trivial disagreement on a remote island in another century: one day, a man decides he doesn’t like another man. The stakes could not be lower, the reason for it little more than one man quietly grappling with his own mortality – the sort of motivation that does not touch the hem of the usual dramatic forces like betrayal or revenge. The conflict is almost indefinable, particularly for those in the heart of it. Even McDonagh’s choice of time and place feels deliberately removed from the world’s troubles, like the inhabitants of Brigadoon parted from civilisation. The characters occasionally hear the sounds of warfare across the sea, but those sounds are as enigmatic as a banshee’s call; the residents on this of this soporifically-tranquil island – one without television or radio or anyone outside communication beyond the occasional letter or newspaper – don’t even seem entirely clear on which side of this distant conflict they’re supposed to be on. The details of it hardly matter. While the threat of violence (tellingly, self-inflicted) soon comes into play, the lack of any familiar form of escalating conflict allows writer/director McDonagh to drill into the philosophy at its heart. When Colin Farrell’s Pádraic demands a drink with his friend, he is actually arguing about what it means to live. The particular, containing the universal. It’s career-best work from both Farrell and Brendan Gleeson, and both Kerry Condon and Barry Keoghan frequently steal the show. Every line is lyrical, most are laugh-out-loud funny, and the cinematography dares you to wish yourself away to this seclusion. Inisherin is McDonagh’s masterpiece.

3. The Fabelmans

3. The Fabelmans

I often think about an interview Michelle Williams gave in which she confessed she never watches the films she is in, because she was too judgmental of her own performance. I found that sad, partly because of the very recognisable insecurity, but largely because it meant she’d missed out on many of the best films of the past twenty years. It must be some kind of Faustian bargain, appearing in Brokeback Mountain, I’m Not There, Synecdoche New York, Manchester By the Sea, Shutter Island, Certain Women, et al, but not actually being able to watch any of them. Now, in possibly her best performance to date, she’s forced to do exactly that, held captive by the images captured by young Sammy – himself destined to become the defining voice of American cinema – reflecting and revealing the truth of her life back to her. It’s no easy task to reckon with either yourself or your past, and it takes very little excavation to find the seams of nostalgia that run through Steven Spielberg’s films. From the kids riding their bikes through Californian suburbia in E.T. to the Boy Scouts in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Spielberg’s personal history has long been strip-mined, but never as explicitly as it is here. He seems to be navigating the hazy path between truth and fact, some moments preserved in the distorting amber of memory, other details are clearly rooted in the specificity of certainty. Moments so vivid, he forces us to feel the scars. Every beat is evocative, from the opening sequence in which young Sammy Fabelman is entranced by Cecil B DeMille’s The Greatest Show On Earth, right through to his fateful meeting with another cinematic hero, in which the secret of his craft is distilled into the what may be the greatest visual joke in cinema history. It is a film that is as comic and tragic as only memory can be, and there’s an element of urgency that I feel we haven’t really seen since Schindler’s List. Even the note-perfect West Side Story felt like the world’s greatest Formula One driver switching up vehicles and executing the perfect motorbike jump, just to see if he can. But Fabelmans is a different beast, the most essential, the most crucial Spielberg has been in years, like this completed work has always existed, waiting to burst out. It’s also as magnanimous a filmmaking crash course as could exist. He couldn’t be more explicit about wanting to share everything he knows. Spielberg knows the secrets and is trying to find a way to tell the rest of us.

2. Hit the Road

2. Hit the Road

“Bring me that apple,” the unnamed father tells the older son as they sit by a river, struggling to give voice to the reality of their situation, a reality neither is fully able to admit. They focus on the fruit. It’s easier that way. Apples do not fall far from the tree, and the feature debut of Panah Panahi – son of the great Iranian director Jafar Panahi – proves it. In Hit the Road, a family drives to an unknown destination, for an unknown reason. The youngest son – an absolute agent of chaos whose irrefutable cuteness covers all sins – fusses over the family dog. Everyone else is in different stages of grief: denial, anger, hope. Panahi does not waste a second, grabbing us by the heart within seconds. He compels us with a mystery, then immediately counters it with family interactions that are funnier than any comedy released this year. Hit the Road is overflowing with scenes that would, on their own, become the defining moment of the film. There’s a conversation about how much the Batmobile would cost in real life that might be the most beautiful scene I’ve seen in anything all year; in another, a cloud of fog rolls in and then out again, approaching and receding with impossible dramatic timing that will haunt me forever. So much of this film has stuck with me: the heady metaphor of the dog’s health, the comedy of the injured cyclist, the stunning performance by Pantea Panahiha as the mother. Every single element, every single frame is so considered, so beautiful, that when it ended I very nearly watched it right through again. With one film, Panah Panahi has established himself to be one of the most exciting filmmakers in the world today.

1. RRR

1. RRR

If I was a Hollywood action director and I watched this film, I would never show my face in public again.

That’s the line I’ve been trotting out to anyone who’ll listen when trying to gin up enthusiasm for RRR – and to be honest, it would be a facetious thing to say even in a year that hadn’t brought Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: The Way of Water. I never really meant it, but enthusiastic hyperbole feels like the right gear when attempting to describe the most unashamedly ridiculous film in living memory.

This wildly over-the-top action film takes two real-life Indian revolutionaries, Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem – both of whom fought against British colonialism in the early 20th century – and imagines a partnership that could conceivably have taken place in the years before they led rebellions that made them both into legends. It’s historical revisionism dressed up as a cartoonish action cinema, and you really don’t need to know more than that setup to appreciate what it’s doing.

About a third of the way into this film, I heard myself do something I generally don’t do: I cackled. The cackle is distinct from a laugh, and there was nothing particularly funny happening at that moment anyway. The cackle was an expulsion of incredulous joy, disbelief that a movie could possibly be this entertaining, this purely fun, and sustain that feeling over such a long running time.

There’s a lot of hemming and hawing that goes into the (ultimately-inconsequential) ranking of these films. In the end, it was the sheer amount of joy I felt in watching RRR that kept it in top position all year. If cinema is all about evoking emotion, I’m not sure I can name another film this year that has done it as effectively as this one. Early on, there’s a meet-cute that involves the most comically-elaborate, physics-defying stunt to save the life of a young boy, and a few scenes later the two are engaged in a hyper-choreographed dance-off with snooty British soldiers. Then later, a guy throws a Bengal tiger at another guy. Why exactly is stopping the rest of cinema from being this entertaining?

I’ve taken a fair bit of joy this year from the look on people’s faces when I insist that they watch a three-hour film almost entirely Telugu, but even more joy from the blanket raves that are inevitably reported back. As cinema tries to work out how to appeal to audiences once again, maybe the secret is simpler than it seems: more revolutions, more dance-offs, and more throwing tigers at guys.

New Release Films Watched in 2022

House of Gucci, Mother/Android, The Tender Bar, Scream, King Richard, The Batman, Murder At Yellowstone City, Nightmare Alley, The Eyes of Tammy Faye, Belfast, Kimi, Deep Water, The King’s Man, Turning Red, Morbius, Windfall, Death on the Nile, The Bubble, Big Bug, Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, The Northman, Everything Everywhere All At Once, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, Parallel Mothers, Cyrano, Top Gun: Maverick, Trees of Peace, Lucy and Desi, Thor: Love and Thunder, Drive My Car, RRR, X, Chip ’N Dale: Rescue Rangers, Gold, The Adam Project, Loveland, Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledor, The House, Ambulance, After Yang, The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, Boiling Point, Fresh, Fire Island, Munich: The Edge of War, Stars At Noon, Crimes of the Future, The Afterlight, Broker, The Gray Man, You Won’t Be Alone, Mr Landsbergis, Moonage Daydream, Nope, Man on Earth, Decision To Leave, Lightyear, Splice Here: A Projected Odyssey, Triangle of Sadness, Flux Gourmet, No Exit, Jurassic World: Dominion, Elvis, Bergman Island, C’Mon C’Mon, Mass, Red Rocket, Benedetta, Petit Maman, My Son, The Lost City, Thirteen Lives, The Drover’s Wife: The Legend of Molly Johnson, Three Thousand Years of Longing, Men, I Came By, Official Competition, The Good Boss, Sundown, Flee, Goodnight Mommy, Gaesterne (Speak No Evil), The Last Thing Mary Saw, Quo Vadis, Aida?, The Duke, Délicieux (Delicious), Cha Cha Real Smooth, Sidney, Lou, The Janes, Mad God, Athena, Persuasion, Blond, Prey, Bullet Train, Navalny, Catherine Called Birdy, The Black Phone, Mr Harrigan’s Phone, The Girl at the Window, Do Revenge, Deadstream, The Good Nurse, The Stranger, Don’t Worry Darling, Fall, Bodies Bodies Bodies, Clerks III, Orphan: First Kill, Hellraiser, Bosch & Rockit, How To Please a Woman, Good Luck To You, Leo Grande, Blaze, Confess, Fletch, Weird: The Al Yankovich Story, Barbarian, Amsterdam, Emily the Criminal, Fire of Love, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, Ticket To Paradise, See How They Run, The Wonder, Glorious, The Desperate Hour, Bros, Wendell & Wild, The Banshees of Inisherin, The Fabelmans, Avatar: The Way of Water, Tár, Ghahreman (A Hero), Holy Spider, An Cialín Ciúin (The Quiet Girl), Im Western nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front), Bardo, falsa crónica de unas cuantas verdades (Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths), The Woman King, Pinocchio, Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio, She Said, “Sr.”, Avec amour et acharnement (Both Sides of the Blade), Strange World, The Humans, Glass Onion, Roald Dahl’s Matilda: The Musical, Armageddon Time, Die Wannseekonferenz (The Conference), Black Adam, Nanny, Resurrection, Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon, Something in the Dirt, Mrs Harris Goes to Paris, L’Événement (Happening), Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Rosaline, Jaddeh Khaki (Hit the Road), We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, Vengeance, Emancipation, White Noise

Older Films Watched in 2022

Cinema Paradiso (Theatrical Cut) (1988), High Society (1956), Room Service (1938), Papillon (1973), The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Scream (1996), Scream 2 (1997), Scream 3 (2000), Scream 4 (2011), Diner (1982), Fanny and Alexander (Theatrical Cut) (1982), My Favorite Year (1982), An Office and a Gentleman(1982), Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), The Beatles: Get Back (2021), Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Halloween III: The Season of the Witch (1982), Ladies and Gentlemen… The Fabulous Stains (1982), The Beast Within (1982), Barbarosa (1982), Q, The Winged Serpent (1982), Victor/Victoria (1982), 48 Hours (1982), Tenebre(1982), Fitzcarraldo (1982), Burden of Dreams (1982), Human Highway (1982), Gandhi (1982), Honkytonk Man (1982), Missing (1982), Identification of a Woman (1982), Smithereens (1982), Chan Is Missing (1982), Made In Britain (1982), The Verdict (1982), Deathtrap (1982), Author! Author! (1982), Making Love (1982), The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), Starstruck (1982), The Man From Snowy River (1982), The Year of Living Dangerously (1982), Freedom (1982), Next of Kin (1982), Turkey Shoot (1982), White Dog (1982), Cat People (1982), Plague Dogs (1982), The Entity (1982), New York Ripper (1982), Night Shift (1982), La note di San Lorenzo (The Night of Shooting Stars) (1982), Still of the Night (1982), A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982), Shoot the Moon (1982), Split Image (1982), Eating Raoul (1982), The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982), Best Friends (1982), Personal Best (1982), Yol (The Road) (1982), The Border (1982), Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1982), The Challenge (1982), The Toy (1982), Losing Ground (1982), Brittania Hospital (1982), De stilte rond Christine M. (A Question of Silence) (1982), Panelkapcsolat (The Prefab People) (1982), Angel (1982), L’ange (The Angel) (1982), Le Beau Mariage (A Good Marriage) (1982), Passion (1982), Une chambre en ville (A Room in Town) (1982), Toute une nuit (All Night Long) (1982), Ba cai Lin Ya Zhen (Plain Jane To the Rescue) (1982), Lung siu yeh (Dragon Lord) (1982), Grease 2 (1982), Tau ban no hoi (Boat People) (1982), Lie huo qing chun (Nomad) (1982), Zain a he pan qing cao qing (The Green, Green Grass of Home) (1982), Hanky Panky (1982), Liquid Sky (1982), Der Fan (The Fan) (1982), Frances (1982), Conan the Barbarian (1982), I Oughta Be In Pictures (1982), Top Gun (1986), Hot Shots! (1991), Gauche the Cellist (1982), Sero hiki no Gôshu (Gauche the Cellist) (1982), The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982), Tempest (1982), Fast Times At Ridgemont High (1982), Labyrinth of Passion (1982), Come Back To the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982), E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial (1982), Blade Runner (Theatrical Cut) (1982), Days of Thunder (1990), Les quartre cents coup (The 400 Blows) (1959), Baisers volés (Stolen Kisses) (1968), Domicile conjugal (Bed & Board) (1970), Crazy, Stupid, Love. (2011), L’amour en fuite (Love on the Run) (1979), Blood Simple (1984), Raising Arizona (1987), Miller’s Crossing (1990), Barton Fink (1991), Fargo (1996), The Big Lebowski (1998), O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), Intolerable Cruelty (2003), The Ladykillers (2004), No Country For Old Men (2007), Burn After Reading (2008), A Serious Man (2009), True Grit (2010), Hail, Caesar (2016), Crimewave (1985), The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), The Naked Man (1999), Gambit (2012), Unbroken (2014), Bridge of Spies (2015), Suburbicon (2017), Encanto (2021), The Lost Daughter (2021), The Jerk (1979), Phantasm (1979), Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), The Tin Drum (1979), Time After Time (1979), Meatballs (1979), …And Justice For All (1979), Escape From Alcatraz (1979), The Visitor (1979), Quadrophenia (1979), Hair (1979), Norma Rae (1979), The Rose (1979), Agatha (1979), Les soeurs Brontë (1979), My Brilliant Career (1979), The In-Laws (1979), 10 (1979), Chilly Scenes of Winter (aka Head Over Heels) (Director’s Cut) (1979), A Little Romance (1979), Going in Style (1979), Wise Blood (1979), The Wanderers (1979), Saint Jack (1979), Old Boyfriends (1979), Last Embrace (1979), When a Stranger Calls(1979), The Amityville Horror (1979), Zombie (1979), Dracula (1979), Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (Nosferatu the Vampyre) (1979), Woyzack (1979), Bildnis einer Trinkerin (Ticket of No Return) (aka Portrait of a Female Drunkard) (1979), Arrebato (Rapture) (1979), Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel (1979), Családi tüzfészek (Family Nest) (1979), Tapage nocturne (Nocturnal Uproar) (aka Night After Night) (1979), Lady Oscar (1979), Série noire (1979), L’enfant secret (1979), Buffet Froid (1979), Dalla nube alla resistenza (From the Cloud to the Resistance) (1979), La Luna (1979), Cristo si è fermato a Eboli (Christ Stopped At Eboli) (Extended Cut) (1979), Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens (1979), The Black Hole (1979), Scum (1979), The Tempest (1979), Radio On (1979), The Human Factor (1979), The Europeans (1979), Fukushû suru wa ware ni ari (Vengeance is Mine) (1979), Taiyô wo nusunda otoko (The Man Who Stole the Sun) (1979), Hao xia (Last Hurrah For Chivalry) (1979), Shan zhong zhuan qi (Legend of the Mountain) (1979), My Winnipeg (2007), Xiao quan guai zhao (The Fearless Hyena) (1979), The Champ (1979), The Main Event (1979), Fast Company (1979), Breaking Away (1979), North Dallas Forty (1979), The Frisco Kid (1979), The Electric Horseman (1979), Butch and Sundance: The Early Years (1979), Heartland (1979), All That Jazz (1979), The Seduction of Joe Tynan (1979), Winter Kills (1979), I…comme Icare (I For Icarus) (1979), The Black Stallion (1979), Cuba (1979), Meteor (1979), Hanover Street (1979), Hardcore (1979), The Great Santini (1979), The Onion Field (1979), Iskanderija… lih? (Alexandra… Why?) (1979), Corps à coeur (Drugstore Romance) (1979), Over the Edge (1979), Chapter Two (1979), The Lady Vanishes (1979), Spider-man (2002), Sürü (The Herd) (1979), Kong shan ling yu (Raining in the Mountain) (1979), More American Graffiti (1979), El caminante (The Traveller) (1979), Natural Enemies (aka Hidden Thoughts) (1979), Tim (1979), Yanks (1979), Le navire Night(1979), The Passage (1979), Mourir à tue-tête (A Scream From Silence) (1979), Siberiade (1979), Rupan sansei: Kariosutoro no shiro (Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro) (1979), The Warriors (1979), Starting Over (1979), Real Life (1979), Amator (Camera Buff) (1979), Kartoteka (1979), The China Syndrome (1979), A Perfect Couple (1979), Quintet (1979), Die dritte Generation (The Third Generation) (1979), Die Ehe der Maria Braun (The Marriage of Maria Braun) (1979), Home Movies (1979), The Brood (1979), Murder By Decree (1979), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (Theatrical Cut) (1979), The Driller Killer (1979), The Muppet Movie(1979), Being There (1979), Alien (Theatrical Cut) (1979), Mad Max (1979), Manhattan (1979), Stalker (1979), Apocalypse Now (Theatrical Cut) (1979), Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), Spider-man 2 (2004), The Love Witch (2016), Dr Who and the Daleks (1965), Dalekmania (1995), Spoorloos (The Vanishing) (1988), The Vanishing (1993), Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads (1983), She’s Gotta Have It (1986), School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Spider-man 3 (2007), The Amazing Spider-man (2012), Mo’ Better Blues (1990), Jungle Fever (1991), Crooklyn (1994), Malcolm X (1992), Clockers (1995), He Got Game (1998), Summer of Sam (1999), Girl 6 (1996), Get on the Bus (1996), Bamboozled (2000), She Hate Me (2004), Miracle at St Anna (2008), Red Hook Summer (2012), Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (2014), Chi-Raq (2015), BlackKklansman (2018), 25th Hour (2002), Inside Man (2006), Oldboy (2013), The Amazing Spider-man 2 (2014), State and Main (2000), Da 5 Bloods (2021), Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Daleks’ Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966), Bo Burnham’s Inside (2021), In Bruges (2008), Spider-man: No Way Home (2021), Wilde (1997), The Happy Prince (2018), West Side Story (2021), The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), Bastardy (2008), A bout de souffle (Breathless) (1960), Une femme est femme (A Woman is a Woman) (1961), Le mépris (Contempt) (1963), Bande à part (Band of Outsiders) (1964), In and Of Itself (2020), Predator (1987), Predator 2 (1990), Predators (2010), The Predator (2018), Dirty Harry (1971), Magnum Force (1973), The Enforcer (1976), Sudden Impact (1983), The Dead Pool (1988), The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976), The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), The Last Tycoon (1976), The Front (1976), Futureworld (1976), The Astrologer (1976), Logan’s Run (1976), The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976), Fantasia (1940), Fantasia 2000 (1999), Welcome To LA (1976), Fighting Mad (1976), News From Home (1976), Nickelodeon (1976), Pressure (1976), Helter Skelter (1976), Snuff (1976), Jack the Ripper (1976), God Told Me To (1976), Two-Minute Warning (1976), Ai no korîda (In the Realm of the Senses) (1976), Inugami-ke no ichizoku (The Inugamis) (1976), Du bi quan wang da po xue di zi (Master of the Flying Guillotine) (1976), Shao Lin men (The Hand of Death) (1976), Insiang (1976), Midway (1976), Tracks (1976), Il deserto dei tartari (The Desert o the Tartars) (1976), The Cassandra Crossing (1976), Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), A Star Is Born (1976), The Bad News Bears (1976), Kenny & Company (1976), The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), The Missouri Breaks (1976), The Shootist (1976), Keoma (1976), From Noon Till Three (1976), The Last Hard Men (1976), God’s Gun (1976), The Great Scout & Cathouse Thursday (1976), The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976), Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976), Mad Dog Morgan (1976), The Devil’s Playground(1976), Don’s Party (1976), Deathcheaters (1976), Storm Boy (1976), Oz (1976), Caddie (1976), Eliza Fraser (1976), Break of Day (1976), Summer of Secrets (1976), Fantasm (1976), Lipstick (1976), Up! (1976), Salon Kitty (1976), Sebastiane (1976), Car Wash (1976), The Human Tornado (1976), The Bingo Long Tavelling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1976), Leadbelly (1976), Emma Mae (1976), Clerks (1994), Clerks II (2006), Orphan (2009), Never Say Die (1939), Freaky Friday (1976), Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), Gator (1976), Grizzly (1976), Squirm (1976), Eaten Alive (1976), Bloodsucking Freaks (1976), Look What’s Happened To Rosemary’s Baby (1976), Alice, Sweet Alice (aka Holy Terror) (aka Communion) (1976), The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976), The Premonition (1976), Burnt Offerings (1976), Never Say Die (1939), To the Devil A Daughter (1976), Satan’s Slave (1976), ¿Quién puede matar a un niño? (Who Can Kill a Child) (1976), La casa dalle finestre che ridono (The House of the Laughing Windows) (1976), Il grande racket (The Big Racket) (1976), Todo Modo (One Way or Another) (1976), Uomini si nasce poliziotti si muore (Live Like a Cop, Die Like a Man) (1976), Cadaveri eccellenti (Illustrious Corpses) (1976), Roma a mano armata (Rome Armed to the Teeth, aka The Tough Ones) (1976), Brutti, sporchi e cattivi (Ugly, Dirty and Bad) (1976), Il Casanova di Federico Fellini (Fellini’s Casanova) (1976), Herz aus Glas (Heart of Glass) (1976), Ansikte mot ansikte (Face To Face) (1976), Mannen på taket (Man on the Roof) (1976), Novocento (1900) (1976), Az ötödik precsét (The Fifth Seal) (1976), Cría cuervos… (1976), Malá morská víla (The Little Mermaid) (1976), Rusalochka (The Little Mermaid) (1976), Bill (2015), Bugsy Malone (1976), L’argent de poche (Small Change) (1976), Une vraie jeune fille (A Real Young Girl) (1976), Die Marquise von O… (The Marquise of O) (1976), Mr. Klein (1976), Duelle (1976), Noroît (une vengeance) (1976), Je t’aime moi non plus (I Love You, I Don’t) (1976), L’aile ou la cuisse (The Wing or the Thigh?) (1976), La Victoire en chantant (Black and White in Colour) (1976), Maîtresse (1976), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Pinocchio (1940)

Short Films Watched in 2022

Antoine et Colette (1962), The Heart of the World (2000), Groot’s First Steps (2022), The Little Guy (2022), Groot’s Pursuit (2022), Groot Takes a Bath (2022), Magnum Opus (2022), How To Sleep (1935), Sunday Night at the Trocadero (1937), A Night at the Movies (1937), Gallopin’ Gals (1940), Mama’s New Hat (1939), Werewolf By Night (2022), The Score (2013), Old Smokey (1938), The Guardians of the Galaxy Holiday Special (2022)