I’m looking forward to the new Criterion edition of Harold and Maude as much as anyone, but I didn’t expect this degree of pandering.

Monthly Archives: June 2012

New Dark Knight Viral Ad

It’s a “Sign”

An Open Letter To St Michael’s Grammar School

Dear St Michael’s,

We’ve never met before, possibly due to the fact that I’m a human and you’re an educational institution, and such a meeting would be logistically and anthropomorphically difficult for the both of us. Nevertheless, I feel compelled to write to you, because you are on the verge of making a decision that will affect the both of us.

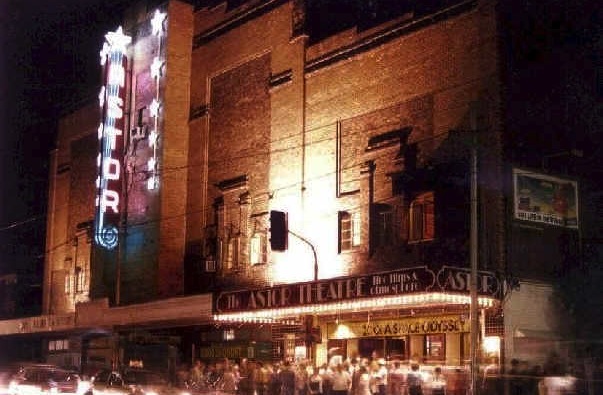

If you don’t know – and I’m guessing you do, but this is an open letter, so we have to assume ignorance on the part of interlopers – a few years ago, you bought the building on the corner of Chapel Street and Dandenong Road. A magnificent art-deco palace that has, for the past 76 years, been the home of The Astor Theatre, an extraordinary single-screen theatre that plays everything from vintage cinema to the latest blockbusters. And yet, it’s so much more than that: it’s an institution. It’s one of the few places you could justifiably call “the heart of Melbourne”. (Although it’s not really situated where the heart would be. Maybe it’s the pancreas of Melbourne. Not as romantic an image, but still a vital organ you really would not want to do without.)

I won’t lie to you. When you bought the building, some of us were a bit nervous. What would that mean for the place that has been so integral to the childhoods, teenagehoods, unnecessarily-awkward twentyhoods, and adulthoods of vast swathes of Melburnians and a surprising number of interstate and international visitors? The last few years have taught me that the formative Astor experiences I thought were so unique are actually universal. There are few people who don’t have at least one important story of life-changing experience that took place within that cinematic cathedral.

Despite our concerns back in 2007, The Astor appeared continued on its journey, and we breathed a collective sigh of relief. This continuation was, it turned out, due to a legally-binding contract and not any form of altruistic charity, but that was of no concern to us. We still had our beloved theatre.

That was five years ago. Now, in 2012, the lease is approaching its expiration, and you guys are moving in. And that frightening sound you heard that followed this revelation was an explosion of community outrage and shock. There were newspaper articles. A massive petition. Somewhat-provocative blogs. There is a forthcoming rally.

You must be wondering what the hell just happened.

I once bought a second-hand car from a guy, and I can tell you that I’d have been quite incensed if, upon conclusion of the transaction, he’d launched a public campaign so he could still drive it around when he wanted. That, by any measure, would have been insane.

So, as you face down a deluge of public negativity the likes of which you have surely never before encountered, I want you to know that I totally understand where you’re coming from.

I totally get that you have a responsibility to your students, teachers, alumni, etc, and that Melbourne Cinephiles With No Actual Connection To St Michael’s is probably further down the list than those of us in that group would like to believe. And you bought that building for a reason; it just makes sense for you to repurpose it.

But you shouldn’t.

In fact, maintaining The Astor in its current form is in your best interest.

As you yourself well know, any educational institution worth its salt is not exclusively concerned with preparing its students for the workforce. Sure, forging a successful career and making money are vitally important skills, but on their own they don’t make for a rounded education or rounded humans. Your own website shows students singing in a choir, experiencing the Transit of Venus, putting on a production of West Side Story, fundraising for children in Uganda… nothing that’s going to get them the CEO job at BP, but incredibly important tools for maintaining their humanity and soul when they find themselves in the dubious position of being CEO at BP.

So how does The Astor figure into this?

You may not know this, but all around the world, cinema is undergoing a massive, unprecedented change. Film is being swapped out for digital in photography, projection and storage. For all the benefits this change offers up – and there are many – there are many, many problems with this, most of which won’t become apparent until it is too late.

The primary one is of preservation.

Digital storage – fast becoming the primary and exclusive method for storing films – is not only more expensive than the storage of physical canisters: it is far more likely to be obsolete. This may seem antithetical, but it is true. (It may also seem hyperbolic. If so, you should read about how close we came to having no footage of the original moon landing.)

But even the supporters of digital-over-film must admit that the change has not been as gradual as it perhaps should have been. The major studios, distributors and exhibitors have backed an almost-overnight switch to the new format, turning traditional film into an historical curio.

Film prints are being digitised and then destroyed. Not sold or given away: destroyed. The ideology that informs such a decision is a frightening one, and comparing it to its obvious historical correlation is probably too incendiary for me to get away with. These prints, once destroyed, can never be recovered. If the importance of this is not hitting you, imagine what would happen if the Louvre announced it would save money on storage by destroying the Mona Lisa and Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin because they’d now scanned them into a computer. The canvas of these pieces is no less vital than the canvasses of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or Leone’s Once Upon a Time In The West or Antonioni’s The Passenger. History is quite literally being demolished by corporations with little sense of an item’s worth beyond the bottom line. And I know using the term ‘corporations’ in this context is often an incendiary pejorative, but it’s an important term because, by its very nature, a corporation tends not to have concerns beyond its own immediate growth. Preserving history and art does not factor into that. Or rather, it will, but by the time this is apparent to them, it will be too late.

Sadly, the number of people within the industry who acknowledge and care about this is too small to have the impact that is needed. And those who do understand the importance do not, on the whole, have an infrastructure available to them to contribute to its preservation. What they have is The Astor.

The Astor has, in fact, managed to upgrade to digital projection – and I say this with my hand on my heart, its 4K digital projection is vastly superior to anything I have seen at any multiplex – whilst still maintaining both 35mm and 70mm projection capabilities. It is the very model of how to embrace the new whilst preserving the old. The Astor takes great care to store film prints that its owners are unable to, and on more than one occasion it has fought tirelessly yet successfully to preserve the last remaining prints of classic movies.

It may seem on the outside as if The Astor is merely one small cinema in a city consumed with wonderful artistic venues, but it is far, far more important than that. It is one of the last remaining outposts in a time of cataclysmic upheaval that has far more dire consequences than most people yet realise.

On Christmas Eve of last year, I went to The Astor to watch a double (projected beautifully on 35mm film) of The Shop Around the Corner (1940) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), two glorious films starring the incomparable Jimmy Stewart. Behind me sat a row of teenagers, and I must confess to a moment of dread when the entered. Would they talk throughout the film? Would their phones come out? Would they be bored?

They were nothing of the sort. They were appreciative, respectful, and – most importantly – engaged. These were kids who had grown up in the age of the internet and smartphones, of frenetically-paced media and attention-destroying pop-culture the like of which we have never seen, collectively enjoying two black-and-white films from the 1940s. Were it not for the legal issues that would have no doubt arisen, I’d have jumped up and hugged them at the end. They gave me a glimmer of hope for the future. And now I wonder if they were, perhaps, students at St Michael’s. It’s not out of the question: they were the right age and they were in the right area. I hope they were.

As a respected and long-standing educational institution, you understand the importance of imbuing your students with essential values. Values that include a respect of the past, an appreciation of long-term worth. And I’m glad you do, because we need more people who recognise the significance of our culture and heritage.

These lessons have, until now, been academic. Now is the time for a practical lesson. Demonstrate how committed St Michael’s is to history, to community, to the arts, to the past and the future.

Your students will receive no greater education.

Sincerely,

Lee

Prometheus, Can You Hear Me?

In the opening moments of Prometheus, a strange, monk-like alien – looking more like a human than the xenomorphs we’re used to from 1979’s Alien, the film with which Prometheus shares a universe – disintegrates himself into a river. It’s a ritual, and it appears to be one of excruciating agony, but he’s inflicted this upon himself on purpose: we don’t know it yet, but he’s creating life.

Prometheus is perhaps the most frustrating film of the year. Not because it does anything particularly bad to the Alien legacy – this is, after all, a franchise that has survived Alien3, Alien Resurrection, and some gigantically-misjudged attempts to combine it with the Predator franchise – but because the great film it could have been is so infuriatingly apparent, you want to take to the thing with a hatchet. Or, rather, the Final Cut Pro equivalent.

One of the many, many great things about the original Alien film is how the crew is made up largely of engineers and miners. These are not scientists with lofty ambition; they’re easily-relatable working stiffs a long way out of their depth. Now, I like films about scientists with lofty ambition, but Hollywood so often fumbles this concept that most of the time I prefer they tried something different. Which is what I was thinking during Prometheus.

One of the many, many great things about the original Alien film is how the crew is made up largely of engineers and miners. These are not scientists with lofty ambition; they’re easily-relatable working stiffs a long way out of their depth. Now, I like films about scientists with lofty ambition, but Hollywood so often fumbles this concept that most of the time I prefer they tried something different. Which is what I was thinking during Prometheus.

Gone is the effortless banter of Alien and characters revealed through action, replaced with some pretty forced characterisation. ‘I ain’t here to make friends!’ proclaims one character for some unknown reason. ‘I just love rocks!’ says another, because his world begins and ends with the fact that he is a geologist. Short of a flashing sign proclaiming such scenes to be CHARACTER MOMENTS, this is pretty excruciating stuff.

Our main protagonists are, in fact, scientists, trying to locate what they believe to be the source of life on Earth. And when Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) – no doubt an alt-universe version of Doctor Who’s scientist Liz Shaw – announces that this multi-year, ultra-expensive expedition is based on her ‘faith’, warning claxons should begin to sound.

‘Faith’ is an interesting topic to explore, but only if you actually take the time to explore it. Simply saying the word ‘faith’ every so often, showing a close-up of a cross from time to time, and waving lazily at what is generally understood to be a conflict between faith and science, is forced and boring, and adds nothing to the story. In fact, it’s so poorly handled that it often detracts.

Additionally, having scientists act in the most unscientific way possible at every turn does not help to paint some faith-based conflict: it just frustrates those of us with even the mildest passing knowledge of how scientists operate.

The film’s biggest problem is this mishandled theme, and it’s even more baffling considering what an inspired triumph its other theme is.

Prometheus is about fatherhood.

Many people have cited Alien as being the ultimate film about childbirth (and, consequently, motherhood). Prometheus – which, again, is set in the same universe as Alien – does not try to directly replicate this idea, but finds an absolutely inspired alternate spin on it.

Many people have cited Alien as being the ultimate film about childbirth (and, consequently, motherhood). Prometheus – which, again, is set in the same universe as Alien – does not try to directly replicate this idea, but finds an absolutely inspired alternate spin on it.

From that opening scene in which a deliberately-male alien creates life, through to the daddy issues felt by both Elizabeth and another character, the man’s role in the creation of life is the topic du jour.

However, unlike the hand-waving tepidness of the faith undertones, the fatherhood theme has a very well thought-out spin: the father is perpetually absent.

Elizabeth’s father, who died when she was young, is physically absent. The other character’s father – and I’m obviously playing awkward pronoun games pains to avoid this minor spoiler – is emotionally absent. And the entire central plot is predicated on the idea of the human race’s father. Where did he go? Why did he create us and then leave? The human race has reached maturity, left home, and is now ready to find out.

As the film played on and I realised where it was going, I became annoyed with a scene that I initially perceived to be a sharp departure from this idea. (A big spoiler is to come, to stop reading now if you haven’t seen it.) When Elizabeth realises something is growing in side of her, she goes to great pains to – let’s not beat around the bush – get an abortion. At first, I imagined this terrifically-tense scene to be a somewhat-clumsy lurch back to the well-trodden theme of motherhood, but this pregnancy is unwanted. Yes, all of the ‘pregnancies’ in the Alien films are unwanted, but none has been so immediately and declaratively rejected as this one. Elizabeth has been violated against her will by a father who has left to pursue his own interests, and must take care of the resulting spawn herself. At first glance, this seems not unlike anything else within the franchise, but the subtext plays completely differently within the context of this film.

And none of this is can be in doubt when the characters overtly refer to the original legend of Prometheus, Greek mythology’s father of mankind.

And none of this is can be in doubt when the characters overtly refer to the original legend of Prometheus, Greek mythology’s father of mankind.

Much of the rest of the film is in as much conflict with itself as the two jostling themes of faith and fatherhood. There may be poorly-depicted characters who react to everything within the stringent prism of their one-sentence outline, but there is also Michael Fassbender’s show-stealing robot David, who manages to be the most interesting and (intentionally) funny character in the entire film. There may be clanging, awkward dialogue, but those battle against some genuinely exciting moments of life. And then there is that ending, which basically encompasses the idea that something good and something bad can merge to create something entirely confusing. It’s easy to appreciate what they were going for, but I’m not convinced the result truly works.

Prometheus is the perfect analogy for the Alien franchise. After an incredible, genre-redefining opening instalment, its father – Ridley Scott – disappeared, and the franchise lost its way. Now they’ve located him again, and, as with the fathers in the film, found him to be extraordinary and disappointing at the same time.